- The Inter-State River Water Disputes are one of the most contentious issues in the Indian federalism today.

- Water is in the State List. It is Entry 17 of the list and hence, states can legislate with respect to rivers.

- Entry 56 of the Union List, however, gives the Central government the power to regulate and develop inter-state rivers and river valleys.

- Article 262 also states that the Parliament may provide for the adjudication of any dispute or complaint with respect to the use, distribution or control of the waters of, or in, any inter-State river or river valley.

- As per Article 262, the Parliament has enacted the following:

- River Board Act, 1956: This empowered the GOI to establish Boards for Interstate Rivers and river valleys in consultation with State Governments. Till date, no river board has been created.

- Inter-State Water Dispute Act, 1956: Under this act, if a state government or governments approach the Centre for the constitution of a tribunal, the government may form a tribunal after trying to resolve the dispute through consultations.

Issues with Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956

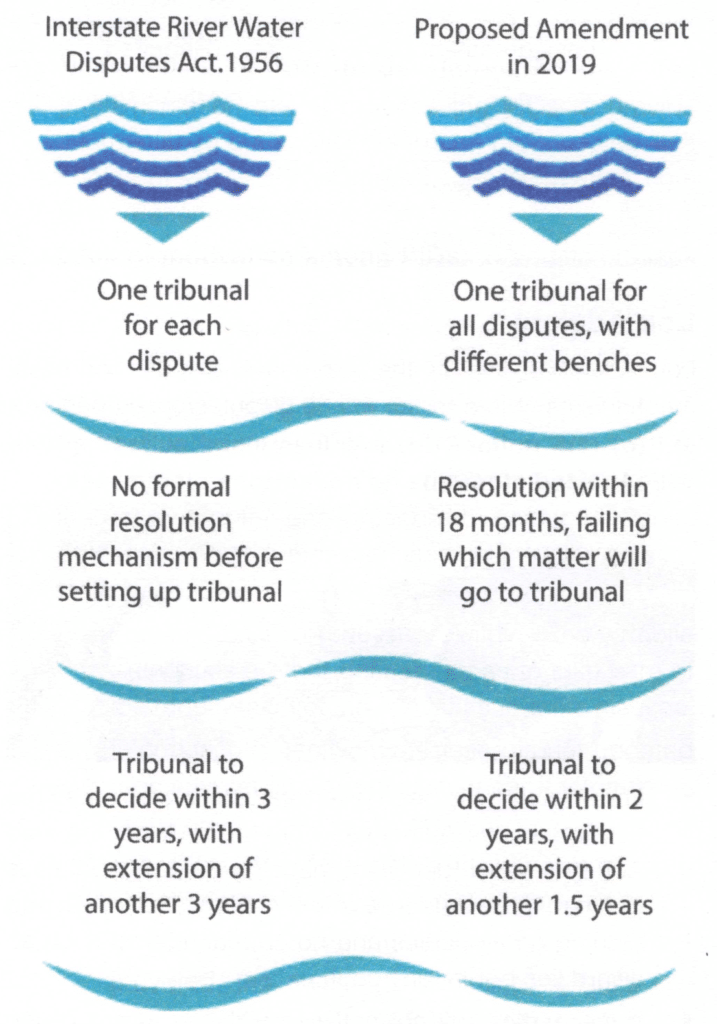

- Multiple Tribunals: Under this Act, a separate Tribunal has to be established for each dispute. There are eight inter-state water dispute tribunals, including the Ravi and Beas Waters Tribunal and Krishna River Water Dispute Tribunal.

- Lacks Robust Governance Framework: Currently there is no time limit for adjudication or publication of reports. There is lack of clarity in the institutional framework and guidelines that define these proceedings to ensure compliance.

- Composition of the tribunals: These are not multidisciplinary and it consists of persons only from the judiciary. There is no upper age limit for the chairman or the members.

- Data Issue: The absence of authoritative water data that is acceptable to all parties currently makes it difficult to even set up a baseline for adjudication.

- Subversion of resolution mechanisms: Though award is final and beyond the jurisdiction of Courts, either States can approach Supreme Court under Article 136 (Special Leave Petition) under Article 32 linking issue with the violation of Article 21 (Right to Life).

- Lack of definitive timeliness: It was amended 17 years ago to make 5 years, the maximum period within which the river water disputes are to be resolved. The reality is something different. In some cases, even after 33 years, the tribunals are yet to give the award.

- Poor enforcement of tribunal awards: Only four of the nine water tribunals could submit their report and the reports also came after huge delays. Only 3 out of 8 tribunal awards have been accepted by the states.

- The multiplicity of tribunals has led to increase in bureaucratic delays and possible duplication of work.

- Judicial interventions: SC taking these disputes under Article 136 which only increases confusion and chaos.

- Politicization of disputes: India’s colonial legacy, complicated federal polity and politicisation of water issue all leads to procedural complexities involving multiple stakeholders across governments and agencies.

Inter-State River Water Disputes(Amendment) Bill 2019

Key Provisions of Inter-State River Water Disputes (Amendment) Bill

- Disputes Resolution Committee (DRC): The bill requires the central government to set up a DRC for resolving any inter-state water dispute amicably. The DRC will get a period of one year, extendable by six months, to submit its report to the central government.

- Members of DRC: Members of the DRC will be from relevant fields, as deemed fit by the central government.

- Permanent Tribunal: The Bill envisages to constitute a standalone Tribunal with permanent establishment and permanent office space and infrastructure. It can have multiple benches. All existing tribunals will be dissolved and the water disputes pending adjudication before such existing tribunals will be transferred to this newly formed tribunal.

- Composition of the Tribunal: The tribunal shall consist of a Chairperson, Vice-Chairperson, and not more than six nominated members (judges of the Supreme Court or of a High Court), nominated by the CJI. The central government may appoint two experts serving in the Central Water Engineering Service, not below the rank of Chief Engineer, as assessors to advise the bench in its proceedings.

- Time allotted to Tribunal to take its decision: Under the Bill, the proposed tribunal has to give its decision on a dispute within a period of two years. This period is extendable by a maximum of one year.

- Decision of the Tribunal: Earlier, the decision of the tribunal must be published by the central government in the official gazette. After publication, the decision has the same force as that of an order of the Supreme Court. Under the Bill, the requirement of publication in the official gazette has been removed.

- The Bill also adds that the decision of the bench of the tribunal will be final and binding on the parties involved in the dispute. This decision will have the same force as that of an order of the Supreme Court.

- Maintenance of data bank and information: The Bill also calls for the transparent data collection system at the national level for each river basin and a single agency to maintain data bank and information system.

- Additional rule -making powers: The Bill gives the central government powers to make rules in which water will be distributed during stress situations arising from shortage in the availability of water.

Key Issues and Analysis of the Bill

- Issues with DRC

- Its role has been elevated from that of a perfunctory “techno-legal” body to an agency with a proactive role.

- An officer of secretary rank will head the DRC and the body will have senior officers from the states that are party to a river water dispute, as members.

- However, there are concerns of it being adequately empowered. There is challenge to make the DRC process neutral and ensure meaningful participation by states that are party to a river water dispute

- There is also lack of clarity whether the DRC function as part of the Permanent Tribunal or will it work separately.

- The Cauvery Supervisory Committee (CSC) which had a similar composition as that of DRC did not have much success

- The DRC aims at a politically negotiated settlement, for river water disputes are deeply political at their core. Its raison d’être is to avoid legal adjudication, not to supplement it. There are doubts whether this can be achieved

- Conflict with Judiciary

- The court had in December 2016 said that it was within its jurisdiction to hear appeals against the 2007 Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal award after the centre and Puducherry opposed the appeals, saying that the Constitution of India expressly disallows the apex court from intervening in interstate river water disputes.

- This means that the party states can now appeal against the decisions of the tribunal.

- The Court followed it up with another order in February 2018 where it modified the allocations of the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal Final award of 2007. The bill does not address the implications of these decisions.

- The bill has to resolve this conundrum first. In simple terms, the Supreme Court says it has jurisdiction over interstate river water disputes while the legislature says it doesn’t.

- Selection of Tribunal Judges

- One cannot miss the inclusion of a committee to select the tribunal judges.

- The committee comprises the prime minister or a nominee as the Chairperson, the Minister of Law and Justice, the Minister of Jal Shakti and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

- This composition will now risk states politicising not just the disputes, but their adjudication by the tribunal. This creates a situation where the dispute could escalate to the Supreme Court.

How 2019 Bill Differs from 1956 Law

thank you so much for this content