The term “Dalit” often appears in news and newspapers. The term, which was, perhaps, first used by Jyotirao Phule in nineteenth century, in context of the oppression faced by the, hitherto “untouchable” castes among the Hindus .literally means “oppressed” in Sanskrit and “broken/ scattered” in Hindi/Urdu. It signified the socio-economic position of untouchables within the country, especially among the Hindus.

The term, later, gained currency amongst the untouchables, who used it to avoid the more derogatory caste names. The contemporary use of the term Dalit has moved away from its earlier meaning of ‘oppression’ faced by the “untouchables” and has become a new political identity. Dalits, in India, through the ages, have organized several movements in different parts of the country for their rights of justice and equality. In order to understand the history of Dalit movements in India, it is important to first, briefly, understand the background and the conditions, especially the caste or ‘jati’ system and the practice of untouchability, which necessitated such movements.

Caste System

In the early Vedic period, appeared the first signs of classification of the society into groups which later took the form of hierarchical classification Varna, based on the profession of the people, into four groups, viz. Brahmin or the priests, the Kshatriyas or the warriors, the Vaishyas or the farmers/traders/merchants and the Shudras or the laburers. In the subsequent periods, the Varna system got entrenched, became hereditary and a fifth category of “untouchables” appeared. During this period, the Varna system lost its relevance and the ‘jati’ (caste) or occupational groups, which were emerging alongside by side the Varna system, gained prominence. The ‘jatis’ or castes were determined by birth and maintained by stringent rules of endogamy and commensality restrictions.

Untouchables and Untouchability

The untouchables included some of the persons who helped perform burials and cremations as well as some hunters and gatherers. The untouchables were considered polluting; forced to live on the fringes of the villages and made to serve the other castes. They were also denied education, entry into temples, ownership of land and access to common resources such as main water bodies of villages.

This systematic and organized practice of social exclusion of certain groups continued for centuries. It was often accompanied by torture, exploitation and violence. All these together led to accumulation of hatred against the upper castes amongst the Hindus.

Pre-Independence

For long, attempts were being made to clear the Indian society of the practice of untouchability. Many reformers like Buddha, Ramanuja, Ramanand, Chaitanya, Kabir, Nanak, Tukaram and others made efforts to end the practice but it continued for centuries, without much change.

However, the genesis of Dalit movements can be dated back to the middle and late Nineteenth century onwards, when breaches began to appear in the caste system, due to various factors such as:

- Economic Changes such as commercialization of agriculture, emergence of new employment opportunities outside the villages, emergence of contractual relations, opportunities in government jobs specially in army etc, together contributed to a shift in the position of untouchables.

- Social reform movements such as those of Sri Narayan Guru in Kerala and Jyotirao Phule in Maharashtra, which started to question the caste inequality and efficacy of caste system.

- Western education , which introduced the Indians to modern ideas of equality, justice and liberty. Dalits began to use the modern values to critique the caste system on the whole and untouchability in particular.

Adi Hindu Movement

In the twentieth-century, ‘Bhakti’ (which means devotion) re-emerged as a caste-based religious expression of the untouchables. This newly-emerged expression of Bhakti was an egalitarian religion of the untouchables which developed into a religious movement in the early 1920s, and argued that Bhakti was a religion of the original inhabitants and rulers of India, the Adi Hindus, from whom the untouchables claimed to have descended.

The new generation of literate untouchables, who led the movement, argued that the social division of labour based on caste status was an imposition forced on Indian society by the Aryan conquerors, who had subjugated the Adi Hindu rulers and made them servile labourers. It can be averred that this new ideology was a direct response to the social constraints imposed on the untouchables which stymied their socio-economic advancement.

The Adi Hindu ideology attracted the mass of the untouchables and was espoused by them, for it provided a historical explanation for the poverty and deprivation of the untouchables and presented a vision of their past power and rights, and hopes of regaining such lost rights. The dalits began to call themselves Adi Hindus in Uttar Pradesh, Adi Andhras in Andhra, and Adi Dharmis in Punjab.

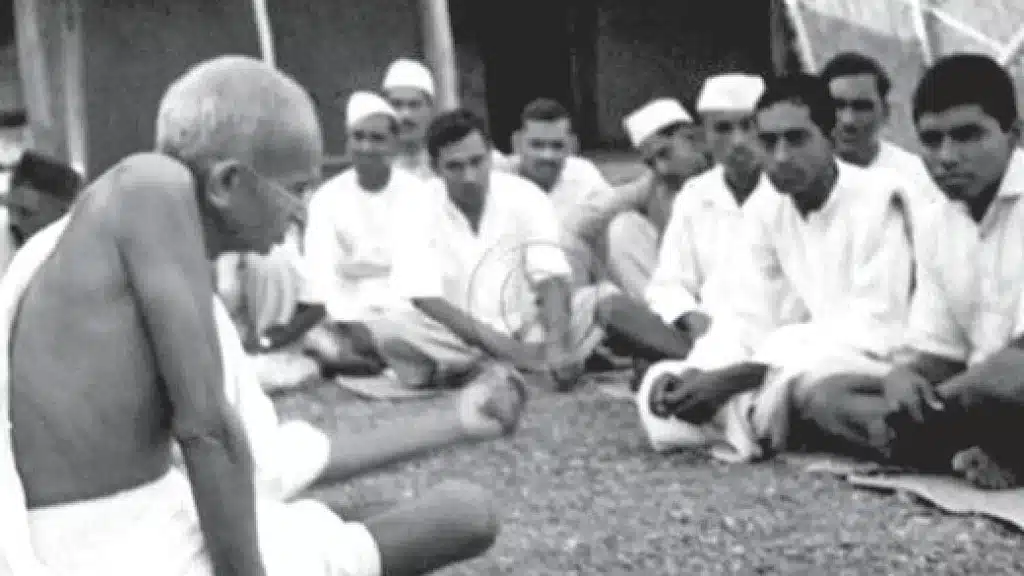

Gandhi and Dalit Movement

In 1920, Mahatma Gandhi, for the first time, highlighted the practice of untouchability as a matter of public concern by inserting an appeal to free Hinduism of the scourge of untouchability in the Nagpur resolution of the Congress. He even launched a campaign for the welfare of the untouchables, which failed to get much support from the upper caste Hindu.

He, later, used the term Harijan meaning people of Hari or God to refer to the untouchables. He became a part of Vaikom (1924-1925) and Guruvayur satyagrahas (1931- 32), which challenged the practice of untouchability. He made constant efforts to make the caste Hindus realize the severity of injustice dealt to the dalits through the practice of untouchability. He, even, opposed the idea of separate electorate, as provide by the Communal Award in 1932, because he believed that once the depressed classes were separated from the rest of the Hindus, there would be no ground to change Hindu society’s attitude towards them.

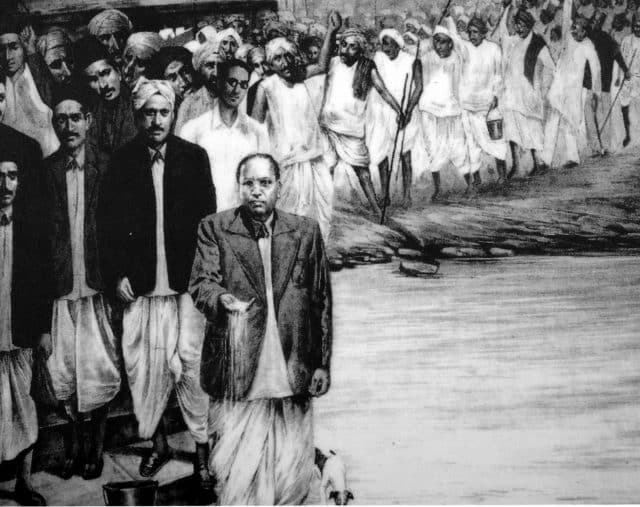

Ambedkar and Dalit Movement

B.R. Ambedkar , an educated dalit belonging to the Mahar community, emerged as a major leader of the dalits in late 1920s. He organized various movements challenging the practice of untouchability. In 1927, he publicly burnt a copy of Manusmriti, the Hindu law book, which authorized untouchability. He demanded a complete overhaul of the Hindu society and theology and asked the dalits to focus

on education and politics rather than seeking redress within the Hindu religion.

In line with his political solution to the problem of untouchability, he demanded a separate electorate

for dalits in the Second Round Table Conference, which led to a major showdown between him

and Gandhi. Although Ambedkar’s demand was honoured in the Communal award (1932), he

later reached an agreement with Gandhi to withdraw his demand of separate electorate for the dalits.

He formed the All India Schedule Caste Federation and Independent Labour Party to mobilize the untouchables. The constitution of All India Schedule Caste Federation claimed distinct and separate from the Hindus. He was critical of Congress and the approach of its leaders and their refusal

to recognize caste system as a political problem.

Post-Independence Developments

Under the traditional Hindu laws, the untouchables (Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes) could not use public places and common provisions such as ponds, pools, parks, wells etc. in addition to many other forms of discrimination.

Despite sincere efforts from a number of reformers, practice of untouchability has been prevalent in India. In order to safeguard the interests of the depressed castes, the Indian Constitution made special provisions to remove their social disabilities and enable them to catch up with the rest of the Indian people in the process of development.

Constitutional Provisions

The Constitution of India guarantees to all its citizens’ equality before law and equal protection of the law. This standard of equality does not permit any discrimination based solely on the caste- characteristics of a person. However, this guarantee is not merely a restriction on state action. It also confers a positive obligation on the state to create a society free of all practices, customs, laws, policies and conditions that impose or have the effect of imposing disabilities on sections of society based on their caste characteristics. The state is duty bound to secure social, economic and political justice for all, and provide for an atmosphere congenial to growth for all.

The major Constitutional provisions which extended and guaranteed the above provisions are:

- Article 14 – guarantees equality before law and equal protection under law of all the citizens irrespective of caste, religion, sex, colour or place of birth.

- Article 15 – prohibits discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth.

- Article 16 – guarantees equality of opportunity and prohibits discrimination with citizens in matters of employment or office under the state on the basis of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth only.

- Article 17 – abolished “untouchability” and made it its practice in any form, punishable by law.

- Article46-enjoins upon the state to promote educational and economic interests of the weaker sections of the people, and, in particular, of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, and, also, protect them from social injustice and all forms of exploitation.

The Constitution also provides for affirmative action, reserving a certain share of seats in favour of the Scheduled Castes in education, employment and legislature, to make up for the historical injustice meted to the people belonging to this group and, also, to allow them to compete with the better of social groups and classes.

Some of the provisions related to the above mentioned reservations are as follows:

- Article 243 D and 243 T – reserve one- third of the seats for SCs and STs in rural and urban local self government institutions respectively.

- Article 330 – reserves seats for SCs and STs in both the houses of the parliament.

- Article 332 – reserves seats for SCs and STs in the state legislative assemblies.

- Article 335 – provides that the claims of the members of SCs and STs shall be taken into consideration in the making of appointments to services and posts in both the Central and State governments.

Article 35(a)(ii) of the Constitution of India established that the parliament shall have and legislature of a state shall not have the power to make law for prescribing punishment for those acts which are declared to be offences under Article 17. Thus, only parliament is empowered to make laws in respect of offences of untouchability, as mentioned under Article 17, so as to ensure uniformity throughout the country.

Besides banning untouchability, the Constitution provides these groups with specific educational and vocational privileges and grants them special representation in the Indian Parliament. In addition to these efforts, the government introduced the Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955 to penalize for preventing people from enjoying a wide variety of religious, occupational, and social rights on the grounds that he or she belongs to Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes.

Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955 (Formerly known as Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955)

Exercising the power conferred by the Constitution under Article 35, in addition to Article 17, the Parliament enacted the Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955.

This act was amended in 1976 and provisions that are more stringent were introduced. The name of the act was changed to Protection of Civil Rights Act.

Punishments for Offences

The following are some of the major offences that are regarded as punishable under the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955:

- Enforcing religious disabilities: The act prescribes punishment for the acts of untouchability with regard to religious activities, viz., worshipping, offering prayers and bathing in a sacred river, etc.

- Enforcing social disabilities: The act prescribes punishment for enforcing social disabilities on the grounds of untouchability under the circumstances like preventing someone access from shops, public restaurants, hotels or places of public entertainment, etc. In addition, preventing an individual from using any river, stream, spring, well, tank, cistern, water-tap or other watering place, or any bathing ghat, burial or cremation ground, any sanitary convenience, any road, or passage, or any other place of public resort which other members of the public have a right to use or have access to.

- Refusing to admit persons to hospitals: The act prescribes punishment for refusing to admit persons to hospitals, dispensaries, educational institutions or any hostel(s).

- Refusing to sell goods or render services in ordinary course of business: The act prescribes punishment for refusing to sell goods or render any service to any person at the same time and place and on the same terms and conditions at or on which such goods are sold or services are rendered to other persons in the ordinary course of business.

- Unlawful compulsory labor: Under the new provision inserted, whoever compels any person, on the ground of untouchability, to do any scavenging or sweeping or to remove any carcass or to flay any animal, or to remove the umbilical cord or to do any other job of a similar nature shall be deemed to have enforced a disability arising out of untouchability.

- Other offences: New types of punishments that may be imposed by the courts under this act like cancellation of licenses in certain cases, resumption or suspension of grants made by the governments, etc

Issues and Challenges

However, the act was not found very effective in the eradication of untouchability and a general feeling of dissatisfaction emerged as the legislation failed to serve the purpose for which it was enacted. The punishments awarded under the act were, also, not adequate. Some of the Issues were, as under:

- It declares untouchability an offence punishable by law, but fails to define the very offence itself.

- It contemplates advancement of the backward classes. However, neither it defines backward classes or the Scheduled Castes nor it provides any specific criteria for such classification.

- The provisions that enable the state for making any special provision for the advancement of the so-called untouchables are ambiguous and most of them are not mandatory.

- Few cases have been filed under the act. The compoundable nature of the offences resulted in compromises and the punishments were small. Most of the victims were reluctant to lodge complaints for fear of social reprisal and harmful economic consequences at the hands of their land lords, money lenders and rural oligarchies who would not give them work or full wages for the work done by them.

Despite amending the act, it failed to fulfil the desired societal goals. Consequently, the government was forced to look for a major revamp in order to check the continuing atrocities and offences against Schedule Castes and Schedule Tribes. Recognizing these existing problems, the parliament passed the “Schedule Caste and Schedule Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989.

Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989

Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 was enacted to prevent atrocities against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. The act prescribes comprehensive measures for protection, welfare and rehabilitation of the victims of the atrocities, in addition to dealing with punishments for atrocities. The act extends to the whole of India except the state of Jammu & Kashmir.

For the effective implementation of the act, the government has set up different administrative agencies, right from state level to district levels. There has been the establishment of Vigilance and Monitoring Committees, Special Courts, Special Public Prosecutors, etc.

Features of the Act

It defines various types of atrocities against SCs/STs and prescribes strict punishment for such atrocities, as under:

- Definition of new types of offences not in the Indian Penal Code (IPC) or in the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955 (PCRA).

- Commission of offences only by specified persons i.e. barbarity can be committed only by non-SCs and non-STs on members of SCs or STs communities. The crimes amongst SCs and STs or between SCs and STs do not come under the purview of this act.

- Establishes special courts for speedy trials of such offences and the rehabilitation of victims.

- A Special Public Prosecutor is appointed to conduct cases in court.

- Under the act, a Court of Session at the district level is deemed a Special Court to provide speedy trials for such offences.

- Enhanced the intensity of punishment for some offences, especially for repeat offenders.

- In addition to increasing the punishment for public servants, the act ensured penalty for delinquency of duties by a public servant.

- Cancellation of arms licenses in the areas identified wherein an atrocity may take place or has taken place and grant of arms licenses to SCs and STs.

- Denial of anticipatory bail and denial of probation to convict of such offences.

- Provides reimbursement, relief , and rehabilitation for victims of atrocities or their legal heirs.

Punishments under the act are graded depending on the severity of the offence and range from six months to life imprisonment, with fine. For certain offences, the act also provides for capital punishment and confiscation of property.

Issues and Challenges

- Inadequate communication and poor coordination between the enforcement authorities at different levels of governance.

- Procedural hurdles such as non-registration of cases.

- Procedural delays in investigation, arrests and filing of charge sheets leading to delay in trial

- Police, instead of filing cases under Prevention of Atrocities Act, files cases under the normal provisions of IPC, which facilities easy bail of the accused persons.

- Low conviction rate of accused, due to hostile role played by investigators.

- Lack of awareness amongst the SCs and STs about their rights. Also, given the strong caste hierarchies in rural areas, many times reluctant to approach police officials, who often belong to dominant castes.

- Seeking justice through special laws is very difficult, as it involves lengthy procedures and it demands adherence to number of procedures at every stage of the case. This, often, turns out to be very costly, tiresome and time-consuming, particularly, for the victims.

- Lack of political commitment and will to effectively implement the act at various levels of governance.

Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes(Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2015

The act has been amended to ensure more stringent provisions for prevention of atrocities against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Key Features

The key features of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2015, are:

- New offences of atrocities have been defined like shaving of head or moustache; garlanding with chappals; denying access to irrigation facilities or forest rights; forcing to dispose or carry human or animal carcasses, or to dig graves, dedicating a Scheduled Caste or a Scheduled Tribe woman as devadasi; abusing in caste names, perpetrating witchcraft atrocities; imposing social or economic boycott; preventing Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes candidates from filing of nomination to contest elections; hurting a Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe woman by removing her garments; forcing a member of Scheduled Caste/Scheduled Tribe to leave his/her house, village or residence; defiling objects sacred to members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes; touching or using words, acts or gestures of a sexual nature against members of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, etc.

- Establishment of exclusive Special Courts and specification of exclusive Special Public Prosecutors also, to exclusively, try the offences under the act to enable speedy and expeditious disposal of cases.

- Power of Special Courts to take direct cognizance of offence and, as far as possible, completion of trial of the case within two months, from the date of filing of the charge sheet.

- Addition of chapter on the ‘Rights of Victims and Witnesses’.

- Definition of clearly the term ‘wilful negligence’ of public servants at all levels, starting from the registration of complaint, and covering aspects of dereliction of duty under this act.

- Addition of presumption to the offences-If the accused was acquainted with the victim or his family, the court shall presume that the accused was aware of the caste or tribal identity of the victim, unless proved otherwise.

Misuse of the Act

Though the Act was introduced with a noble idea, the anti-atrocities law, which protects Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes from casteist slurs and discrimination, has been used as an instrument to “blackmail” innocent citizens and public servants in many cases. Some of the misuses are as under:

- False Complaints: As observed by the Supreme Court, instead of blurring caste lines, the act has been misused to file false complaints to promote caste hatred through false implication of innocent citizens on caste lines. Consequently, the Supreme Court said that the current working of the act may even “perpetuate casteism”, if not brought in line.

- Penal Provisions: The 1989 act penalises casteist insults and even denies anticipatory bail to the suspected offenders. The law is, therefore, used to rob a person of his personal liberty merely on the unilateral word of the complainant. The court observed that an anticipatory bail shall be allowed if the accused is able to, prima facie, prove that the complaint against him, is malafide.

The apex court referred as to how public administration has been threatened by the abuse of this act. Many public servants find it difficult to give adverse remarks against employees belonging to SCs and STs for fear that they may be charged under the act.

Misuse and Weak Implementation

The Supreme Court recently asserted that the SCc/ STc (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 has become an instrument of “blackmail” and is being used by some to exact “vengeance” and satisfy vested interests. However, this also reflects weak implementation by the concerned

authorities and judiciary.

National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data shows a high number of complaints and charge sheets with a low conviction rate or high acquittals indicating the existence of false complaints. As per NCRB data, final reports submitted by the police during the year 2016, revealed

that the police had found 2150 cases to be true but with insufficient evidence. 5,347 cases to be “false”, and 869 cases to be “mistakes of fact”.

Similarly, data on disposal of cases by police and courts revealed that under the act, 11,060 cases were taken up for investigation in 2016, and the charge-sheeting rate was 77%. However, in 4546 cases of which the trials were completed, there were only 701 convictions with 3845

acquittals meaning the conviction rate was 15.4 % while the pendency percentage went at a staggering 90.5%.

Though the intention of the court was to protect officers from “arbitrary arrest”, and to protect innocent citizens from being falsely implicated in cases, data from NCRB and the Ministry of Home Affairs shows that if conviction rates under the act are low, it may have as much to do with the misuse of the provision as with the manner in which investigations are conducted and

cases prosecuted in the courts.

Way Forward

India has a large number of delayed cases due to procedural delays in investigation, delayed prosecution and high percentage of acquittals. In order to ensure that the benefits reach the vulnerable sections, including the SCs and the STs, special steps need to be taken on the following lines:

- Wide spread publicity needs to be done through enhanced use of media highlighting the offences and punishments covered under the act.

- As India is a vast country with different languages, the clauses of acts must be disseminated in vernacular languages.

- Copies of the act should be widely distributed so that they are available easily, including every police station of the country.

- Orientation, trainings and seminars should be conducted regularly to sensitize officials at all levels of the administration to discuss the objectives of the act and effective implementation.

Conclusion

In India, SCs and STs have suffered social ostracization and economic deprivation for centuries. To address this social deficit and to ensure that the dignity of the individual belonging to SCs to STs remains intact, the Constitutionmakers made several, provisions in, the Constitution. Article 17 abolished untouchability and made it ‘an offence punishable in accordance with law’.

However, despite the existence of several laws, the abhorrent practice of discrimination and violence against the SCs and STs continues as the traditional divisions between different caste groups seen to persist at all levels of Indian society. However, with the enactment of The Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2015, India can hope to see some positive change in the direction of reducing social inequality, if the above mentioned law is implemented sincerely and expeditiously, both in letter and spirit.

Ambedkar and Dalit Buddhist Movement

Ambedkar had considered accepting to Sikhism and even appealed other leaders of scheduled castes but he rejected this idea after meeting leaders of the Sikh community and concluding that his conversion might result in having a “second-rate status” amongst Sikhs.

In 1956, he went back to conversion, as being the only feasible option to ameliorate the conditions of the dalits. First, he, his wife and some of his followers accepting Buddhism and, then, he himself led close to half a million people, mostly Mahars, into Buddhism. This conversion gave rise to ‘Dalit Buddhist Movement’, wherein Ambedkar radically re-interpreted Buddhism and created a new sect of Buddhism called ‘Navayana1.

The Buddhist movement was somewhat hindered by Dr. Ambedkar’s death shortly after his conversion. It did not receive the immediate mass support from the ‘untouchable’ population that Ambedkar had hoped for. Divisions and lack of direction amongst the leaders of the Ambedkarite movement have been an additional impediment.

Later, in 1980, the Dalit Buddhist movement gained impetus with the arrival of Dipankar, a ‘Chamar bhikkhu’. Dipankar had come on a Buddhist mission in Kanpur and his first public appearance was scheduled at a mass conversion drive in 1981.

Dalit Panthers

In the early 1970s, an organization calling itself the ‘Dalit Panthers’ was formed with the project of instituting classbased dalit politics. Dalit Panther as a social organization, was founded by Namdev Dhasal in April 1972 in Mumbai; it was a part of countrywide wave of radical politics which reflected in use of creative literature to bring out the plight of dalits. Though the movement took birth in the slums of Mumbai, it spread out to cities and villages throughout the country, proclaiming revolt.

Panthers gave a call for the unity of dalit politicians under Ambedkar ‘s movement, and they attempted to counter violence against untouchables in the villages. They also stirred public attention through the emerging Dalit Sahitya, the ‘literature of the oppressed’. Dalit Panthers rapidly became popular and mobilized dalit youth and students and insisted that they use the term dalit as against any other available term for self-description. In course of time, Panthers became an important political force, especially in the cities.

Post Emergency of 1975-77, serious differences started to emerge in the organization over whether or not to include non-dalit poor and non-Buddhist dalits. Thereafter, this cult faded.

Bahujan Samaj Party

In North India, a new political party called Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) emerged in 1980s under the leadership of Kanshi Ram (and, later, Mayawati who went on to become the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh). BSP declared electoral power as its basic strategy and aim, which can be seen in its political history, where BSP (which is a Dalit-based party) is willing to ally with any mainstream political party to further its political power and agenda.

BSP succeeded in gaining sufficient political base in states such as Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Punjab which raised its significance in coalition politics.

In 2007, Mayawati was successful in winning clear majority in Uttar Pradesh assembly elections, becoming the first dalit party to do so without any external support.

Dalit Capitalism

At a conference in Bhopal in 2002, dalit intellectuals argued that the retreat of the state in the era of globalization will bring diminishing returns, if they depended only on reservations. Since then, dalit intellectuals have espoused that capital is the best way to break caste in the modern economy. The argument has been supported by the fact that successive census reports on non-agricultural enterprises show that dalits own far fewer businesses than they should, commensurate with their share of the total Indian population.

Dalit control, of means of production, more broadly referred to as ‘Dalit Capitalism’, has also been proposed as means to dalit emancipation from the clutches of social discrimination prevalent in India even after decades of various noble Constitutional provisions guaranteeing SCs equality and justice in the country. In recent years, this attempt, to be entrepreneurs amongst the dalits, has been gaining

momentum. The government, too, has initiated a number of schemes such as MUDRA Yojana and Stand-Up India.

Other developments

Non-dalit parties have also played a significant role in empowerment of dalits. Different NGOs and agricultural labour unions have taken up issues such as wage demand, demand for employment guarantee, right to education, abolition of child labour, etc. which have contributed towards dalit empowerment.

Exclusive organizations such as Ambedkar Sanghams in rural areas and other student youth office associations in urban areas, have worked tirelessly for betterment of dalits.

Impact and Analysis

The position of SCs in general has improved. However, this success cannot be attributed to either reservation or conversion, which are two of the most visible strategies. It is seen that Buddhist converts in villages have not given up their old gods and goddesses, and they still celebrate their festivals in the same way, they used to do before. Thus, despite conversion it is apparent that dalits feel equality only when they are able to practice the religious rites that were earlier denied to them. It is, also, seen that those who have converted to Christianity and Islam still face the same discrimination they did while in Hinduism; in short, conversion has only transferred the problem and not solved it. In this context, Gandhi’s understanding of struggle against the dalit plight that emphasized gaining religious equality via temple entry and reforming the caste system from within, stands validated to some extent.

Effect of reservation as a strategy has, also, not been very successful in bringing equitable growth even within the schedules castes. Reservation in jobs and educational institutions (especially in higher studies) has only been marginally successful because the total percentage of population that opts for higher education, and those employed in formal sector, is very low. Also, the benefits of reservation are availed by those sections of SCs which are better-off and leave the underprivileged wanting. This has

led to further demand of quotas within quotas.

Hence it can be deduced that, though, the situation for SCs has improved, but the causes for the improvement are more broad based.

The process of socio-economic change industrialization, globalization, schemes such as rural employment guarantee scheme, right to education, mid-day meal system, the extension of primary health and education centers, the campaign of abolition of child labour, etc has been crucial in raising the overall status of dalits in the society.

Land redistribution, where it has occurred, has reduced the stigma attached to landlessness. The delinking of caste system attached to traditional occupation has also been critical in this emamcipation of dalits.

As a result of many such initiatives, untouchability in urban areas has virtually disappeared and is on a decline in rural areas, especially in those rural areas where the opportunities for employment have increased.

Atrocities against SC’s still continue but now they are mostly as reaction to open defiance of upper caste norms. Having mentioned that, it is important to mention that inequalities still remain in employment, social opportunities and education. It is seen that the link between caste and literacy is strong which can be seen in overall literacy rate of lower castes, especially that of women. It is possible to reduce this inequality only through positive social measures, such as compulsory primary and even secondary education and employment guarantee schemes, amongst others.

nice analysis