We, human beings have, seriously altered and endangered the environment in our evolution from the primitive phase, when both we and our livelihoods were determined by the environment we lived in, to the modern phase today, when we are constantly tampering with it, for a better human civilisation. The consequences of our meddling with the environment, mostly for our own benefits and ease of life, are becoming ubiquitous in the form of global warming, climate change and loss of biodiversity, rather mass extinctions, amongst other similar phenomenas.

The awareness of our detrimental actions has dawned upon us and concerted action has begun to preserve the environment and even reverse the damages done. The human race has together initiated a number of programmes to this end. More recently, in 2015 a climate pact was reached in Paris with an aim to control the global rise in temperature and prevent the concomitant disastrous impact on the human civilisation and our only planet, which sustains life, the Earth.

The environment prevention and protection movements have history of their own both within India and world. In this chapter, we will look at genesis and evolution of environmental movements in the country and discuss some of the major environmental movements in the country. Finally, we will analyse the role of women in the environmental movements in the country.

Historical underpinnings

Pre-History

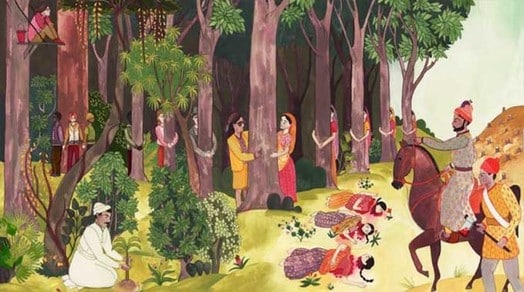

Environment, the sum of range of complex physical, chemical, and biotic factors, has had a privileged position throughout the history of human civilisation in the Indian sub-continent. Beginning with the nature worship, also evident in many other primitive societies, to non-violent traditions of Buddhism and Jainism which preached nonkilling of animals and even plants. In 1730, Amrita Devi Bishnoi and more than 300 others belonging to Bishnoi sect, sacrificed their lives in protests of felling of Khejarli trees in Rajasthan. This is the earliest noted incident for own market protection in India.

The British, in their pursuit of furthering Britain’s economic interests, first regulated the forests and then promoted commercial exploitation of the forests, which was resented by the tribal forest dwellers. In fact, the genesis of concern for environmental protection in India can be traced back to the early twentieth century when people, especially forest dwellers, protested against the commercialization of forest resources during the British colonial period.

Beginnings

However, it was only in the 1970s that a coherent and a relatively organized awareness of the ecological impact of state’s monolithic development process started to develop and grow into a fully-fledged understanding of the limited nature of natural resources and to prevent the depletion of such natural resources. The origins of Indian environmental movement can be traced to the critique of nationalized economic development that gathered momentum in the aftermath of Jayaprakash Narayan’s ‘total revolution’ movement of the 1970s.

Although colonial rule throughout the world was accompanied and supported by exploitation of forest and environmental destruction, independence of India from the British colonial rule did not stop any of these processes. Rather, the disruption of the relationships between local societies and their natural resources bases, has continued in the worldwide movement toward modernisation, as in India.

India in comparison to Western countries

Unlike in the West, where modern environmentalism was given birth to, by scientists; in India, it began through the protests of rural communities.

There was an unequal competition over resources such as forests, fish, water , and pasture. On one side were local communities who depended on these resources for subsistence; on the other, were urban and industrial interests who appropriated them for commerce and profit. State policies tended to favour the latter, leading to protests that called for a fairer and more sustainable use of the gifts of nature.

Reasons for the emergence of environmental movements in India

Some of the important reasons for the emergence of environmental movements in India, are:

- Control over natural resources.

- Ineffective developmental policies of the government.

- Socioeconomic reasons.

- Environmental degradation/ destruction.

- Spread of environmental awareness and media.

Ramchandra Guha, an eminent environment historian, lists three events which occurred within the country, in 1973, that facilitated debate on environmental issues in India:

- In April 1973, the government of India announced the launching of Project Tiger, an ambitious conservation programme aimed at protecting the country’s national animal.

- The publication of an article in Economic and Political Weekly, in 1973, entitled “A Charter for the Land” authored by B. B. Vora, a high official in the Ministry of Agriculture in government of India, which drew attention to the extent of erosion, water logging and other forms of land degradation in the country.

- In 1973, in Mandal, a remote Himalayan village, a group of peasants stopped a group of loggers from felling a stand of trees by hugging the trees. This event sparked a series of similar protests through the 1970s, collectively known as “Chipko” movement. A large number of environmental movements have emerged in India, especially after 1970s. These movements have grown out of a series of independent responses to local issues, in different places at different times.

Chipko Movement

| Year | 1973 |

| Place | Garhwal district of Uttrakhand |

| Leaders | Sunder Lai Bahuguna, Gaura Devi, Bachni Devi, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Shamsher Singh Bisht and Ghanasyam Raturi. |

| Aim | To protect the trees on the Himalayan slopes from the axes of contractors of the forest. |

Background

In early 1973, the forest department allotted ash trees, of the Alaknanda catchment area in the mid-Western Himalayas, to a private company for commercial logging. Earlier the forest department had refused permission to the villagers, around the forest, to fell the same ash trees for making agricultural tools. This government action favouring commercial interests enraged the villagers and provoked the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Sangha (DGSS), a local cooperative organization, to fight against this injustice by lying down in front of timber trucks andburning resin and timber depots, as was done during the Quit India movement. When these methods were found unsatisfactory, Chandi Prasad Bhatt, one of the leaders, suggested embracing the trees to prevent them from being cut.

Protest

On 27th of March 1973, a group of peasants embraced the tress in a remote Himalayan village, to stop a group of loggers from felling a patch of trees. Thus, there was born the Chipko movement, and through it, the modern Indian environmental movement itself.

Demands

Chipko movement had six demands-one of which was banning of commercial cutting of trees. The other demands included:

- On the basis of minimum needs of the people, a reorganization of traditional rights should take place.

- Arid forests should be made green with people’s participation and increased tree cultivation.

- Village committees should be formed to manage forests.

- Forest related home-based industries should be developed and the raw materials, money and techniques for it, should be made available.

- Based on local conditions and requirements, local varieties should be given priority in afforestation.

Government response

The government bowed to the relentless protests of the villagers and finally banned felling of trees in the Himalayan regions for fifteen years, until the green cover was fully restored.

Significance

- The movement focused world’s attention on the environmental problems.

- With its success, the environment movements spread to other neighbouring areas.

- It used consensual, non-violent direct action/strategy of clinging on to the trees as a response against the violent action of felling the trees by the contractors.

- The movement drew thousands of women into its fold, as the forest contractors usually doubled up as suppliers of alcohol to men in the region.

- It became a symbol of many such popular demands in different parts of the country during 1970s and later. The Appiko movement in Karnataka (discussed later in the chapter) was inspired by this movement

Silent Valley Project

| Year | 1978 |

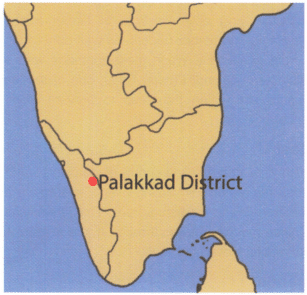

| Place | Silent Valley, an evergreen tropical forest in the Palakkad district of Kerala. |

| Leaders | The Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP), an NGO, and the poet activist Sughathakumari |

| Aim | To protect the Silent Valley, the moist evergreen forest from being destroyed by a hydroelectric project |

Background

Silent Valley in Kerala is a rich 89 square kilometers biological treasure trove in the vast expanse of tropical virgin forests on the green rolling hills. In 1970s, a 200 MW hydroelectric dam on the river Kunthipuzha under the Kundremukh project was to come up. The proposed project was deemed to be ecologically unviable, as it would drown a chunk of the valuable rainforests of the valley and threaten the life of a host of endangered species of both flora and fauna.

Protest

The Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (KSSP), an NGO working in the region for three decades amongst masses of Kerala to create environmental awareness, began a campaign to stop the Silent Valley Hydel Power Project in 1978. The campaign to save Silent Valley turned out to be a public education programme in many respects. The protestors demanded the protection of the tropical rainforests and maintenance of the ecological balance.

Government response

In May 1979, Morarji Desai, the then Prime Minister of India, directed the state government to expedite the completion of the project. Many environmentalists including the noted ornithologist Salim Ali voiced their objections. The International Union of Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) also registered its disapproval. A public interest litigation case was filed in the High Court which was, however, dismissed subsequently. Finally, in December 1980, the Kerala government announced the scrapping of the project. The Silent Valley was declared as a National Park.

Significance

- The Silent Valley movement contributed to the growth of environmental consciousness amongst the people of Kerala.

- The success of the ‘Save Silent Valley’ movement became the inspiration for similar agitations, including the Narmada Bachao Andolan and protests against the Tehri Dam.

- The movement permanently shifted the equilibrium of the debate over environment, making it difficult for green-unfriendly measures to succeed in the state.

Jungle Bachao Andolan

| Year | 1982 |

| Place | Singhbhum district of Bihar (now in Jharkhand). |

| Leaders | The tribals of Singhbhum. |

| Aim | To protect the sal forest in the region. |

Background

The Jungle Bachao Andolan took shape in the early 1980s when the government proposed to replace the natural sal forest of Singhbhum district, Bihar, with commercial teak plantations. The movement, which spread to nearby states, has highlighted the gap between the forest department’s aims and the people’s wishes.

Appiko Movement

| Year | 1983 |

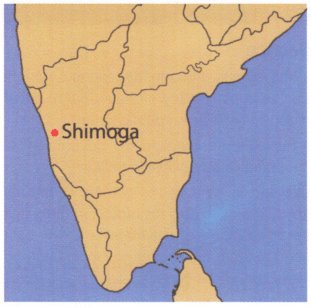

| Place | Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts of Karnataka state. |

| Leadres | Pandurang Hegde helped launch the movement in 1983. |

| Aim | Against the felling and commercialization of natural forest and the ruin of ancient livelihood. |

Background

Karnataka’s Uttar Kannada which forms part of the Western Ghats is known as the ‘forest district’. The area has rich forest wealth with a typical micro climate for cash crops such as black pepper and cardamom. During the colonial rule, the rich forest resources were exploited; the teak trees were felled to build ships and timber and fuel woods were sent to Mumbai. After independence, the government also began felling trees for revenue and the forest department, which continued the colonial forest policy, converted the primeval tropical forests into monoculture teak and eucalyptus plantations.

Protest

A group of youth in Balegadde village, protesting against moves to establish teak plantations, wrote to forest officials asking them to stop clearing the natural forest. But their appeal was ignored. Then the villagers decided to launch a movement. They invited S. L. Bahuguna, the architect of Chipko movement, and gathered local people to take up oath to protect trees by embracing them. In September 1983, when the axe-men came for felling trees in the Kalase forests, people embraced the trees and, thus, the ‘Appiko’ movement was launched. Appiko means ‘hugging’ in Kannada. The protests continued for 38 days, after which the government finally withdrew the felling orders.

Objectives

The objectives of Appiko movement were:

- Protecting the existing forest cover.

- Regeneration of trees in denuded land.

- Utilizing forest wealth with proper consideration to conservation of natural resources.

Significance

- The movement created awareness amongst the villagers throughout the Western Ghats about the ecological danger posed by the commercial and industrial interests to their forest, which was the main source of their sustenance.

- Since the movement, people, now, closely monitor the exploitation of the forests by the forest department and have been able to highlight discrepancies in the professed and actual forest management practices.

- It forced the government to change its forest policy. Some specific changes include ban on clear felling, no further issuing of concessions to logging companies, and moratorium on felling of green trees in the tropical rainforests of Western Ghats.

- The success of this agitation spread to other places and the movement was launched in eight areas covering the entire Sirsi forest division in Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts.

Narmada Bachao Andolan

| Year | 1985 |

| Place | Gujarat, M.P. and Maharashtra. |

| Leaders | Medha Patekar, Baba Amte, adivasis, farmers, environmentalists and human rights activists. |

| Aim | A social movement against a number of largedams being built across Narmada River and the consequent damage to the environment. |

Background

In early 1980s the government launched a project to construct 30 big,135 medium sized and around 3000 small dams on Narmada and its tributaries that flow across Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Maharashtra. Narmada Bachao Andolan, a loose collective of local voluntary organisation, began a movement opposing the constructions of Sardar Sarovar Project, one of the two biggest projects planned in that area.

Sardar Sarovar Project

It is a multipurpose mega-scale dam built on the Narmada river near Navagam, in Gujarat. The dam provides water for drinking and irrigation purposes, generates electricity and facilitates effective flood and drought control in the region. The dam submerged around 245 villages in the state and required relocation of around two and a half lakh people from these villages. The relocation and rehabilitation of the project affected people and became a major cause of tussle between local activists and the government.

Protests

The movement began with a protest for not providing proper rehabilitation and resettlement for the people displaced by the construction of Sardar Sarovar Dam. Later on, the movement turned its focus on the preservation of the environment and the eco-systems of the Narmada valley. Activists also demanded the height of the dam be reduced to 88 m from the proposed height of 130m. In the wake of increasing protests, World Bank, the funding agency for the project, withdrew from it.

The Narmada Bachao Andolan has drawn upon a multiplicity of discourses for protests such as:

1. Displacement risks and resettlement provisions.

2. Environmental impact and sustainability issues.

3. Financial implications of the project.

4. Forceful evictions and violations of civil liberties.

5. Issues pertaining to river valley planning. The movement used various tools of protests such as Satyagraha, Jal Samarpan, Rasta Roko, Gaon Bandh, demonstrations and rallies, hunger strikes and blockade of projects.

Government response

The protest had long demanded reduction of height of the dam, which had stalled project for over three decades. The NDA government, in June 2014, gave the final clearance and dam was, finally, inaugurated on 17th September, 2017.

Significance

- The movement, through its efforts, brought larger issues such as efficacy of the model of development and public interests on public forum.

- The movement compelled the government to relook and revamp its rehabilitation policy.

- It was and is, still, as the leaders of the movement continue their protests for reduction of its height and better assessment of the benefits and impact on the people, longest continuing environmental movement in the history of the country.

- The journey of the movement depicted a gradual process of disjunction between political parties and social movements in India.

Environment and Women

A lot of studies on women and environment have shown that women are significant actors in natural resource management and they are major contributors to environmental rehabilitation and conservation. In addressing some key environmental problems, women play a dominant role. Women, through their roles as farmers and as collectors of water and firewood, have a close connection with their local environment and often suffer most directly from environmental problems.

Women, particularly those living in rural areas or mountain areas, have special relationships with the environment. They are more close to the nature than men and this very close relationship makes them perfect managers of ecosystems. The Indian women were, always, ahead in the matter of prevention of pollution and protection, preservation, conservation promotion and enhancement of the environment. The strong desire, devotion and dedication towards better environment made Indian women crusaders against environment pollution.

Women, in our country, have brought a different perspective to the environment debate, because of their different experience base. In fact, they have led some of the major environmental movements in the country from the forefront, such as:

- Amrita Devi gave up her life with her daughter’s Ashu, Ratni and Bhagu in the year 1730 to save green trees which were being felled by the then Maharaja of Jodhpur, at place Khejarli of Marwar in Rajasthan. More than 363 Bishnois (people belonging to Bishnoi sect), also, gave up their lives for saving Khejarli trees and this incident has gone done in history as Bishnoi Movement.

- The Chipko movement, as we have already seen, witnessed a large women participation. Women of the villages resisted, embracing trees to prevent their felling to safeguard their lifestyles, which were

dependent on the forests. - Narmada Bachao Andolan, which focused on the preservation of the environment, and the eco-systems of Narmada valley, was led by Medha Patekar and saw large women participation in various protests, held during the course of the movement.

- It is important to recall the names of Indian women who have fought legal battles in the court of law for environment protection, as Mrs. Sarla Tripathi of Indore, Kinkari Devi of Sirmour district, Krishna Devi of Rajasthan, etc.

- In 2007, Radha Behen and other activists, along with villagers embarked on a padayatra to the source of Kosi in Uttarakhand. It was during this walk that they became aware of the scale of the threat to Uttarakhand rivers. Since then, the Uttarakhand Nadi Bachao Andolan has continued its bitter fight against the government.

Critical analysis of environmental movements

Robert Nisbet says that when the history of the twentieth century shall be finally written, the single most important social movement of the period shall be judged to be ‘environmentalism’. It is no longer possible to treat ecology and international political economy as separate spheres.

Positives

In India, the environmental movements have grown rapidly over the last three to four decades and have played a key role in three areas such as:

- In creating public awareness about the importance of bringing about a balance between environment and development.

- In opposing developmental projects that are inimical to social and environmental concerns.

- In organizing model projects that show the way forward towards non-bureaucratic and participatory, community-based natural resource management systems.

- The environmental movements through their persistence and perseverance have compelled the government to change its policies and realign the development strategies to a sustainable path.

- A notable aspect of the environmental movements in India has been its association with the voluntary organisations.

- A number of community organisations have emerged in the course of these environmental movements, which are actively working for inclusive and sustainable development, in different parts of the country.

- These movements have played a key role in bringing Indian women from remote areas in the socio-political sphere by drawing them in the movements and even allowing them to lead protests on issues which affect their livelihoods.

Negatives

- The environmental movements have been blamed for stalling developmental projects in the country and perceived as being anti-developmental and regressive in nature.