It has been recognised across the globe that good governance is essential for sustainable development, both economic and social. The three essential aspects emphasised in good governance are transparency, accountability and responsiveness of the administration. Citizen charter and RTI are two important steps which not only help in boosting transparency and accountability but also improves citizen administration interface.

Citizen Charter

The Citizens Charter is an instrument which seeks to make an organization transparent accountable and citizen friendly. A Citizens’ Charter is basically a set of commitments made by an organization regarding the standards of service which it delivers.

Citizen Charter represents a systematic effort to focus on the commitment of the Organisation towards its Citizens in respects of Standard of Services, Information, Choice and Consultation, Non-discrimination and Accessibility, Grievance Redress, Courtesy and Value for Money.

Every citizens charter has several essential components to make it meaningful; the first being the Vision and Mission Statement of the organization.

- This gives the outcomes desired and the broad strategy to achieve these goals and outcomes. This also makes the users aware of the intent of their service provider and helps in holding the organization accountable.

Secondly, in its Citizens’ Charter the organization must state clearly what subjects it deals with and the service areas it broadly covers.

- This helps the users to understand the type of services they can expect from a particular service provider. These commitments/promises constitute the heart of a citizens’ charter.

Even though these promises are not enforceable in a court of law each organization should ensure that the promises made are kept and in case of default a suitable compensatory/remedial mechanism should be provided.

Thirdly, the Citizens’ Charter should also stipulate the responsibilities of the citizens in the context of the charter . The Citizens’ Charter when introduced in the early 1990’s represented a landmark shift in the delivery of public services. The emphasis of the Citizens’ Charter is on citizens as customers of public services.

Origin of Citizen Charter

The Citizens’ Charter scheme in its present form was first launched in 1991 in the UK. The aim was to ensure that public services are made responsive to the citizens they serve. In the “Introduction to the First Report on Citizens’ Charter” that was released by Prime Minister John Major in 1992 it was clearly defined as follows.

- “The Citizens’ Charter sees public services through the eyes of those who use them. For too long the provider has dominated and now it is the turn of the user. The Citizens’ Charter will raise quality increase choice secure better value and extend accountability (Cabinet Office. U.K. 1992)”.

A Citizens’ Charter is a public statement that defines the entitlements of citizens to a specific service the standards of the service the conditions to be met by users and the remedies available to the latter in case of non-compliance of standards. The Charter concept empowers the citizens

in demanding committed standards of service. Thus, the basic thrust of Citizens’ Charter is to make public services citizen centric by ensuring that these services are demand driven rather than supply driven. In this context the six principles of the Citizens’ Charter movement as originally framed were:

- Quality: Improving the quality of services;

- Choice: For the users wherever possible;

- Standards: Specifying what to expect within a time frame;

- Value: For the taxpayers’ money;

- Accountability: Of the service provider (individual as well as Organization);

- Transparency: In rules, procedures schemes and grievance redressal.

These were revised in 1998 as nine principles of service delivery in the following manner:

- Set standards of service;

- Be open and provide full information;

- Consult and involve;

- Encourage access and promote choice;

- Treat all fairly;

- Put things right when they go wrong;

- Use resources effectively;

- Innovate and improve; and

- Work with other providers.

Indian Experience

Government of India in 1996 commenced a National Debate for Responsive Administration. A major suggestion which emerged was bringing out Citizens’ Charters for all public service organisations. The idea received strong support at the Chief Ministers’ Conference in May 1997; one of the key decisions of the Conference was to formulate and operationalise Citizens’ Charters at the Union and State Government levels in sectors which have large public interface such as Railways, Telecom, Post & Public Distribution Systems , Hospitals and the Revenue & Electricity Departments.

The momentum for this was provided by the Department of Administrative Reforms & Public Grievances (DAR & PG) in consultation with the Department for Consumer Affairs. The Department of AR & PG simultaneously formulated guidelines for structuring a model charter as well as a list of do’s and don’ts to enable various government departments to bring out focused and effective charters.

| Key Principles of Citizen Charter | |

|---|---|

| Six principles of original Citizen’s Charter Movement (1991) | Nine principles of ’Service First’ (1998) framed by Labour govt., UK |

| Quality: Improving quality of services Choice: Wherever possible Standards: Specify what to expect and how to act if standards are not met Value: For the tax payers money Accountability: Individual and organizations Transparency:Rules/ procedures/ schemes/ grievances | Set standards of service Be open, provide full information Consult and involve Encourage access and promotion of choice Treat all fairly Put things right when they go wrong Use resources effectively Innovate and improve Work with other providers |

In May 1997, the programme was launched in India by different ministries, departments . Directorates and other organizations at the Union level have formulated 115 Citizens’ Charters. There were 650 such Charters developed by various Departments and agencies of the State Governments and Union Territories (as on February 2007).

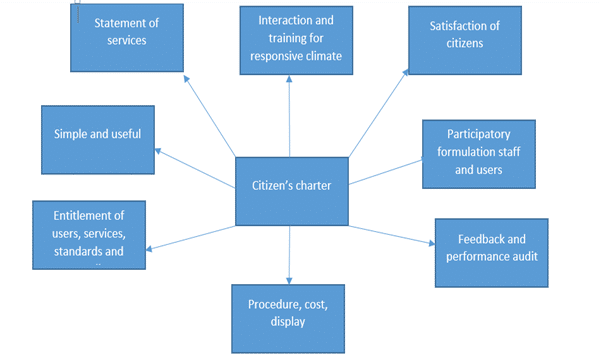

The DARPG set out a series of guidelines to enable the service delivery organisations to formulate precise and meaningful Charters to set the service delivery parameters. These were as follows:

- To be useful the Charter must be simple;

- The Charter must be framed not only by senior experts but by interaction with the cutting edge staff who will finally implement it and with the users (individual organizations);

- Merely announcing the Charter will not change the way we function. It is important to create conditions through interaction and training for generating a responsive climate;

- Begin with a statement of the service(s) being offered;

- A mention is made against each service about the entitlement of the user service standards and remedies available to the user in case of non-adherence to standards;

- Procedures/costs/charges should be made available on line/display boards/ booklets/inquiry counters etc at places specified in the Charter ;

- Indicate clearly that while these are not justiciable the commitments enshrined in the Charter are in the nature of a promise to be fulfilled with oneself and with the user;

- Frame a structure for obtaining feedback and performance audit and fix a schedulejor reviewing the Charter at least every six months; and

- Separate Charters can be framed for distinct services and for organizations/ agencies/attached or subordinate to a Ministry/Department.

Some of the recommendations for charter formation were:

- Need for citizens and staff to be consulted at every stage of formulation of the Charter.

- Orientation of staff about the salient features and goals/ objectives of the Charter; vision and mission statement of the department; and skills such as team building, problem solving, handling of grievances and communication skills.

- Need for creation of database on consumer grievances and redress.

- Need for wider publicity of the Charter through print media, posters, banners, leaflets, handbills, brochures, local newspapers etc., and also through electronic media.

- Earmarking of specific budgets for awareness generation and orientation of staff and for replication of best practices in this field.

Nodal Department: The Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances (DARPG) of the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions, Government of India, to provide a more responsive and citizen-friendly governance, coordinates the efforts to formulate and operationalise Citizens’ Charters.

- The Right of Citizens for Time Bound Delivery of Goods and Services and Redressal of their Grievances Bill, 2011 (Citizens Charter) was introduced to create a mechanism to ensure timely delivery of goods and services to citizens.

Review of Citizens’ Charter

- Poor design and content:

- Most organizations do not have adequate capability to draft meaningful and succinct Citizens’ Charter. Most Citizens’ Charters drafted by government agencies are not designed well. Critical information that end-users need to hold agencies accountable are simply missing from a large number of charters. Thus, the Citizens’ Charter programme has not succeeded in appreciably empowering end-users to demand greater public accountability.

- Devoid of Participative Mechanisms:

- In a majority of cases, CC is not formulated through a consultative process with cutting edge staff who will finally implement it.

- Lack of public awareness:

- While a large number of public service providers have implemented Citizens’ Charter only a small percentage of end-users are aware of the commitments made in the Citizens’ Charter. Effective efforts of communicating and educating the public about the standards of delivery promise have not been undertaken.

- Inadequate groundwork:

- Government agencies often formulate Citizens’ Charters without undertaking adequate groundwork in terms of assessing and reforming its processes to deliver the promises made in the Charter.

- Charters are rarely updated:

- Charters reviewed for this report rarely showed signs of being updated even though some documents date back from the inception of the Citizens’ Charter programme nearly a decade ago. Only 6% of Charters reviewed even make the assurance that the document will be updated some time after release. In addition, few Charters indicate the date of release. Needless to say, the presence of a publication date assures end-users of the validity of a Charter’s contents.

- End-users and NGOs are not consulted when Charters are drafted:

- Civil society organizations and end-users are generally not consulted when Charters are being formulated. Since a Citizens’ Charter’s primary purpose is to make public service delivery more citizen-centric- agencies must investigate the needs of end-users when formulating Charters by consulting with ordinary citizens and civil society organizations.

- The needs of senior citizens and the disabled are not considered when drafting Charters:

- Just one Charter reviewed for this report assured equitable access to disabled users or senior citizens. Many agencies actually do cater to the needs of the disadvantaged or elderly, but do not mention these services in their charter.

- Resistance to change:

- The new practices demand significant changes in the behavior and attitude of the agency and its staff towards citizens. At times, vested interests work for stalling the Citizens’ Charter altogether or in making it toothless.

- Measurable Standards of Delivery are Rarely Defined: Making it difficult to assess whether the desired level of service has been achieved or not.

- Lack of Interest: Little interest is shown by the organizations in adhering to their CC since there is no citizen friendly mechanism to compensate the citizen if the organization defaults.

- Uniformity in CC: Tendency to have a uniform CC for all offices under the parent organization. CCs have still not been adopted by all Ministries/Departments. This overlooks local issues.

Increasing Effectiveness

2nd ARC has briefly dealt with the issue of Citizens’ Charters in its Fourth Report on ‘Ethics in Governance’. The Commission observed that in order to make these Charters effective tools for holding public servants accountable the Charters should clearly spell out the remedy/penalty/ compensation in case there is a default in meeting the standards spelt out in the Charter. It emphasized that it is better to have a few promises which can be kept than a long list of lofty but impractical aspirations.

- Internal restructuring should precede Charter formulation:

- As a meaningful Charter seeks to improve the quality of service mere stipulation to that effect in the Charter will not suffice. There has to be a complete analysis of the existing systems and processes within the organization and if need be these should to be recast and new initiatives adopted. Citizens’ Charters that are put in place after these internal reforms will be more credible and useful than those designed as mere desk exercises without any system re-engineering.

- One size does not fit all:

- This huge challenge becomes even more complex as the capabilities and resources that governments and departments need to implement Citizens’ Charters vary significantly across the country. Added to these are differing local conditions. The highly uneven distribution of Citizens’ Charters across States is clear evidence of this ground reality. For example, some agencies may need more time to specify and agree upon realistic standards of service. In others, additional effort will be required to motivate and equip the staff to participate in this reform exercise. Such organizations could be given time and resources to experiment with standards grievances redressal mechanisms or training. They may also need more time for internal restructuring of the service delivery chain or introducing new systems. Therefore, the Commission is of the view that formulation of Citizens’ Charters should be a decentralized activity with the head office providing broad guidelines.

- Wide Consultation Process:

- Citizens’ Charters should be formulated after extensive consultations within the organization followed by a meaningful dialogue with civil society. Inputs from experts should also be considered at this stage.

- Firm commitments Jo be made:

- Citizens Charters must be precise and make firm commitments of service delivery standards to the citizens/consumers in quantifiable terms wherever possible. With the passage of time an effort should be made for more stringent standards of service delivery.

- Redressal mechanism in case of default:

- Citizens Charter should clearly lay down the relief which the organization is bound to provide if it has defaulted on the promised standards of delivery. In addition, wherever there is a default in the service delivery by the organization, citizens must also have recourse to a grievances redressal mechanism. This will be discussed further in the next chapter on grievances redressal mechanisms.

- Periodic evaluation of Citizens’ Charters:

- Every organization must conduct periodic evaluation of its Citizens’ Charter preferably through an external agency. This agency while evaluating the Charter of the organisation should also make an objective analyses of whether the promises made therein are being delivered within the defined parameters. The result of such evaluations must be used to improve upon the Charter. This is necessary because a Citizens’ Charter is a dynamic document which must keep pace with the changing needs of the citizens as well as the changes in underlying processes and technology. A periodic review of Citizens’ Charter thus becomes an imperative.

- Benchmark using end-user feedback:

- Systematic monitoring and review of Citizens’ Charters is necessary even after they are approved and placed in the public domain. Performance and accountability tend to suffer when officials are not held responsible for the quality of a Charter’s design and implementation. In this context end-user feedback can be a timely aid to assess the progress and outcomes of an agency that has implemented a Citizens’ Charter. This is a standard practice for Charters implemented in the UK.

- Hold officers accountable for results:

- All of the above point to the need to make the heads of agencies or other designated senior officials accountable for their respective Citizens’ Charters. The monitoring mechanism should fix specific responsibility in all cases where there is a default in adhering to the Citizens’ Charter.

- Include civil Society in the process:

- Organizations need to recognize and support the efforts of civil society groups in preparation of the Charters their dissemination and also facilitating information disclosures. There have been a number of States where involvement of civil society in this entire process has resulted in vast improvement in the contents of the Charter its adherence as well as educating the citizens about the importance of this vital mechanism.

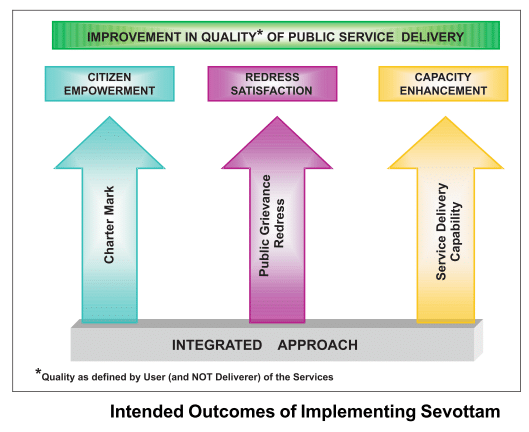

Sevottam Model

Department of the Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances, GOI has come out with a framework for improving delivery of public services, which is known as the Sevottam framework and the same is presented below.

The framework is the Indian Standard IS: 15700:2005 of delivery of public services. It is a quality management framework which provides a systematic approach to improving public service and any public organization may acquire the said certification by complying with the steps.

The Sevottam framework is applicable to all public services delivered by the central and state governments.

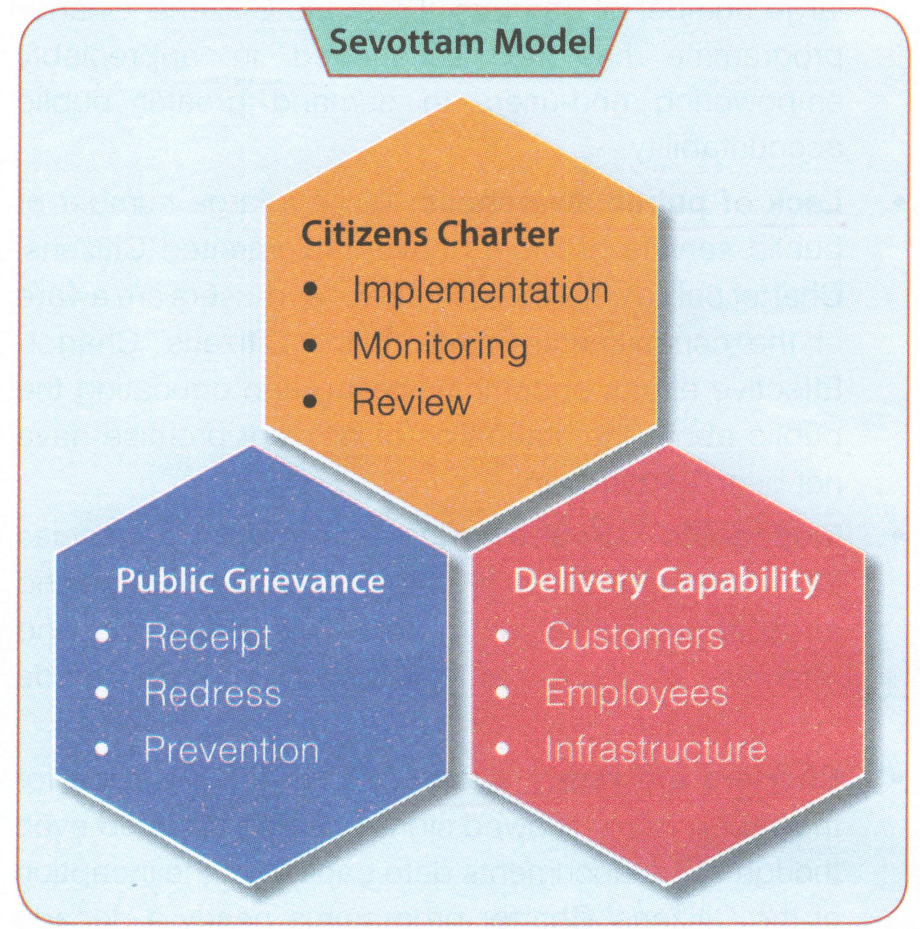

The framework has three different modules as shown below:

- Citizen Charter for defining the level of services to be provided to the citizen.

- Improving capability for delivery of services to the desired standard.

- Grievance redress standard

The rationale of the Sevottam Framework is that the service standard should be defined first so that every citizen knows what to expect in terms of service types and standards. The next task is to receive feedback and complaints from the clients to know what has gone wrong in not meeting the service standard. The third task is to meet the service standard by developing capability of the delivery system.

A New Approach for Making Organizations Citizen Centric

The Citizens’ Charter cannot be an end in itself it is rather a means to an end – a tool to ensure that the citizen is always at the heart, of any service, delivery mechanism. The IS 15700: 2005 of the Bureau of Indian Standards is an Indian Standard for Quality Management Systems. The Standard stipulates that a Quality Management System helps an organization to build systems which enable it to provide quality service consistently and is not a substitute for ‘service standards’. In fact they are complementary to each other.

The Sevottam model seeks to assess an organization on

- (i) implementation of the Citizens’ Charter;

- (ii) implementation of grievances redressal system and;

- (iii) service delivery capability.

The Sevottam model is in the take off stage. It has been pointed out that a model to make administration citizen centric should be easy to understand both by the citizens and the organizations.

Therefore, prescribing a rigid model and implementing it, following a top-down approach is not always the best option. Since the maximum interaction of citizens takes place with field formations, it is necessary that reforms for enshrining a citizens’ centric administration take place at that level rather than following a trickle down approach by concentrating on reforms at the apex level.

The same approach is also necessary for Citizens’ Charter. Today most of the field formations either do not have a Citizens’ Charter or they adopt a generic one provided by the Headquarters.

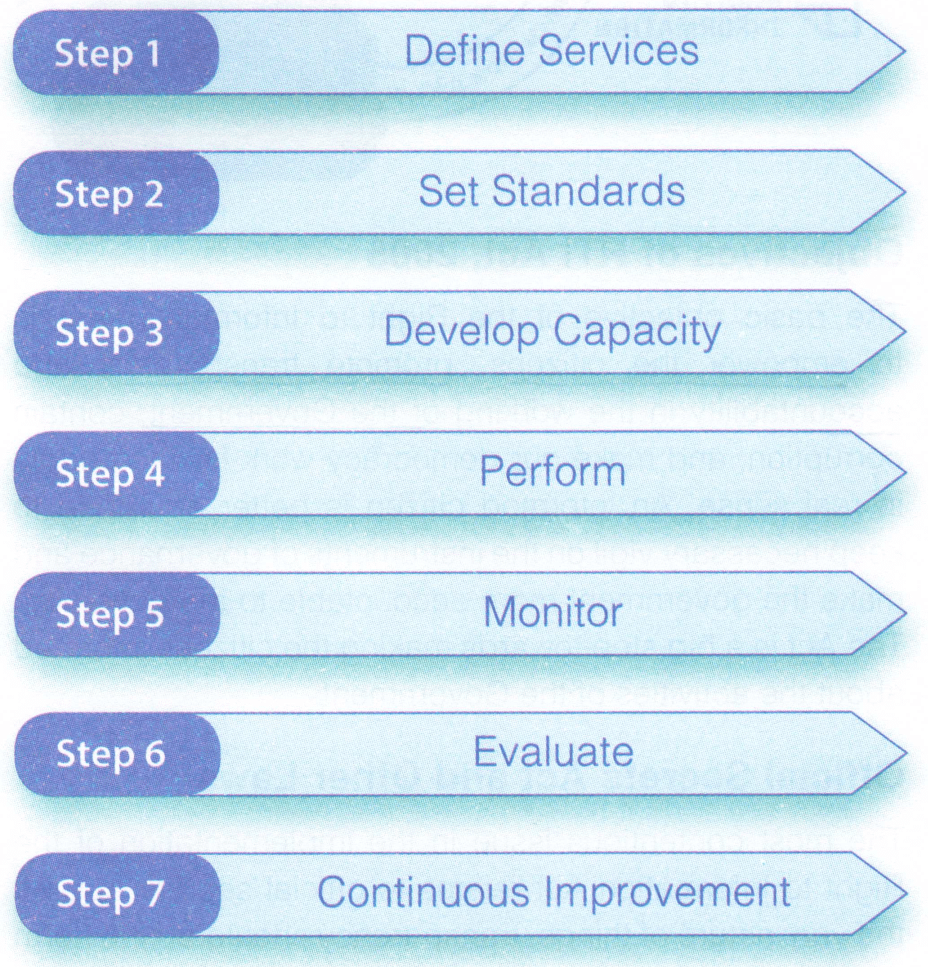

The ARC Seven Step Model for Citizen Centricity

This model draws from the principles of the IS 15700:2005, the Sevottam model and the Customer Service Excellence Model of the UK. Each organization should follow a step by step approach which would help it in becoming increasingly more citizen centric. This approach should be followed not only by the top management but also by each unit of the organization that has a public interface.

The top management has the dual responsibility of setting standards for itself as well as guiding the subordinate offices in setting their own standards. Besides, all supervisory levels should ensure that the standards set by the subordinate offices are realistic and are in synergy with the broad organizational goals. Thus, though each office would have the autonomy to set standards, these would have to be in consonance with the organizational policies.

Step 1: Define Services

- All organizational units should clearly identify the services they provide. Here the term service should have a broad connotation. Enforcement departments may think that enforcement is not a service. But this view is not correct. Even the task of enforcement of regulations has many elements of service delivery like issue of licenses, courteous behaviour etc. Normally, any legitimate expectation by a citizen should be included in the term ‘service’.

- Defining the services would help the staff in an organization in understanding the links between what they do and the mission of the organization. In addition, the unit should also identify its clients and if the number of clients is too large it should categorize them into groups, which would be the first step in developing an insight into citizens’ needs.

Step 2: Set Standards

- It has been well said that ‘what cannot be measured never gets done’. Once the various services have been identified and defined, the next logical and perhaps the most important step is to set standards for each one of these services.

- A good starting point would be getting an input from the clients as to what their expectations are about each one of the identified services. Thereafter, based on their capability the organization’s overall goals and of course the citizens’ expectations, the unit should set standards to which they could commit.

- It is very important that these standards are realistic and achievable. Complaints redressal mechanism should form an integral part of this exercise. These standards should then form an integral part of the Citizens’ Charter.

Step 3: Develop Capacity

- Merely defining the services and setting standards for them would not be sufficient unless each unit has the capability for achieving them.

- Moreover since the standards are to be upgraded periodically. It is necessary that capacity building also becomes a continuous process. Capacity building would include conventional training but also imbibing the right values, developing a customer centric culture within the organization and raising the motivation and morale of the staff.

Step 4: Perform

- Having defined the standards as well as developed the organizational capacity, internal mechanisms have to be evolved to ensure that each individual and unit in the organization performs to achieve the standards.

- Having a sound performance management system would enable the organizations to guide individuals’ performance towards organizational goals.

Step 5: Monitor

- Well articulated standards of performance would be meaningful only if they are adhered to. Each organization should develop a monitoring mechanism to ensure that the commitments made regarding the quality of service are kept.

- Since all commitments have to form a part of the Citizens’ Charter, it would be desirable that an automatic mechanism is provided which signals any breach of committed standard, is would involve taking corrective measures continuously till the system stabilizes. Compliance to standards would be better if it is backed up by a system of rewards and punishments.

Step 6: Evaluate

- It is necessary that there is an evaluation of the extent of customer satisfaction by an external agency, is evaluation could be through random surveys, citizens’ report cards, obtaining feedback from citizens during periodic interactions or even an assessment by a professional body. Such an evaluation would bring out the degree to which the unit is citizen centric or otherwise.

- It would also highlight the areas wherein there have been improvements and those which require further improvement. This would become an input in the continuous review of the system.

Step 7:Continuous Improvement

- Continuous improvement in the quality of services is a continuous process. With rising aspirations of the citizens, new services would have to be introduced, based on the monitoring and evaluation, standards would have to be revised and even the internal capability and systems would require continuous upgradation.

The Commission is of the view that the approach outlined in the model described is quite simple and there should be no difficulty for any organization or any of its units to adopt this approach and make it citizen centric. Commission would like to recommend that the Union Government as well as State Governments should make this model mandatory for all public service organizations.

Excellent article

Relevant article

Topclass ,…material, sir I have one request pls do have an ient history available ,… pls urgent request,…and of economics also