Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act (AFSPA) is a Parliamentary act that grants special powers to the Indian Armed Forces and the state and paramilitary forces in areas classified as “disturbed areas”. The objective to implement the AFSPA Act is to maintain law and order in disturbed areas.

According to the Disturbed Areas (Special Courts) Act, 1976 once declared ‘disturbed’, the area has to maintain status quo for a minimum of 6 months.

Background:

- The AFSPA – like many other controversial laws – is of a colonial origin. The AFSPA was first enacted as an ordinance in the backdrop of the Quit India Movement launched by Mahatma Gandhi in 1942.

- A day after its launch on August 8, 1942, the movement became leaderless and turned violent in many places across the country. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, VB Patel and a host of others had been put behind the bars.

- Shaken by the massive scale of violence across the country, the then Viceroy Linlithgow promulgated the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Ordinance, 1942.

- This Ordinance practically gave the Armed Forces a “license to kill” when faced with internal disturbances.

- On the lines of this ordinance, the Indian government promulgated four ordinances in 1947 to deal with internal security issues and unrest arising due to partition in four provinces Bengal, Assam, East Bengal and the United Provinces.

- The ordinances were replaced by an Act in 1948 and the present law effective in the Northeast was introduced in Parliament in 1958 by the then Home Minister, G.B. Pant.

- It was known initially as the Armed Forces (Assam and Manipur) Special Powers Act, 1958.

- After the States of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland came into being, the Act was adapted to apply to these States as well.

The Indian Parliament has enacted three different acts under Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) for different regions

1. Armed Forces Special Powers (Assam and Manipur) Act, 1958

- AFSPA was first enacted to deal with the Naga insurgency in the Assam region.

- In 1951, the Naga National Council (NNC) reported that it conducted a “free and fair plebiscite” in which about 99 per cent of Nagas voted for a ‘Free Sovereign Naga Nation’. There was a boycott of the first general election of 1952 which later extended to a boycott of government schools and officials.

- In order to deal with the situation, the Assam government imposed the Assam Maintenance of Public Order (Autonomous District) Act in the Naga Hills in 1953 and intensified police action against the rebels. When the situation worsened, the state government of Assam deployed the Assam Rifles in the Naga Hills and enacted the Assam Disturbed Areas Act of 1955, thus providing a legal framework for the paramilitary forces and the state police forces to combat insurgency in the region. But the Assam Rifles and the state police forces could not contain the Naga rebellion and the rebel Naga Nationalist Council (NNC) set up a parallel government in 1956.

- To tackle this threat, The Armed Forces (Assam and Manipur) Special Powers Ordinance 1958 was promulgated by President Dr. Rajendra Prasad on 22 May 1958. It was later replaced by the Armed Forces (Assam and Manipur) Special Powers Act of 1958.

- The Armed Forces (Assam and Manipur) Special Powers Act, 1958 empowered only the Governors of the States and the Administrators of the Union Territories to declare areas in the concerned State or the Union Territory as ‘disturbed’.

- The reason for conferring such power as per “Objects and Reasons’” included in the Bill was that “Keeping in view the duty of the Union under Article 355of the Indian Constitution, interalia, to protect every State against any internal disturbance, it is considered desirable that the Central government should also have the power to declare areas as ‘disturbed’, in order to enable its armed forces to exercise special powers”.

- It was later extended to all North-Eastern states.

2. The Armed Forces (Punjab and Chandigarh) Special Powers Act, 1983

- The central government enacted the Armed Forces (Punjab and Chandigarh) Special Powers Act in 1983, by repealing The Armed Forces (Punjab and Chandigarh) Special Powers Ordinance of 1983, in order to enable the central armed forces to operate in the state of Punjab and the union territory of Chandigarh which was battling the Khalistan movement in the 1980s.

- In 1983 the Act was enforced in the whole of Punjab and Chandigarh. The terms of the Act broadly remained the same as that of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (Assam and Manipur) of 1972 except for two sections, which provided for additional powers to the armed forces –

- Sub-section (e) was added to Section 4 stipulating that any vehicle can be stopped, searched and seized forcibly if it is suspected of carrying proclaimed offenders or ammunition.

- Section 5 was added to the Act specifying that a soldier has the power to break open any locks “if the key thereof is withheld”.

- As the Khalistan movement died down AFSPA was withdrawn in 1997, roughly 14 years after it came ito force. While the Punjab government withdrew its Disturbed Areas Act in 2008, it continued in Chandigarh until September 2012 when the Punjab and Haryana high court struck it down.

3. The Armed Forces (Jammu and Kashmir) Special Powers Act, 1990

- The AFSPA in Jammu & Kashmir was enacted in 1990 in order to tackle the unprecedented rise in militancy and insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir.

- If the Governor of Jammu and Kashmir or the Central Government, is of opinion that the whole or any part of the State is in such a disturbed and dangerous condition then this Act can be imposed.

- Jammu and Kashmir has its own Disturbed Areas Act (DAA) separate legislation that came into existence in 1992. Even after the DAA for J&K lapsed in 1998, the government reasoned that the state can still be declared as a disturbed area under Section (3) of AFSPA.

- Implementation of AFSPA in J&K has become highly contentious but it still continues to be in operation.

Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA)

- It gives powers to the army, state and central police forces to shoot to kill, search houses and destroy any property that is “likely” to be used by insurgents in areas declared as “disturbed” by the home ministry.

- AFSPA is invoked when a case of militancy or insurgency takes place and the territorial integrity of India is at risk.

- Security forces can “arrest a person without a warrant”, who has committed or is even “about to commit a cognizable offence” even based on “reasonable suspicion”.

- It also provides security forces with legal immunity for their actions in disturbed areas.

- While the armed forces and the government justify its need in order to combat militancy and insurgency, critics have pointed out cases of possible human rights violations linked to the act.

- The law first came into effect in 1958 to deal with the uprising in the Naga

- The Act was amended in 1972 and the powers to declare an area as “disturbed” were conferred concurrently upon the Central government along with the States.

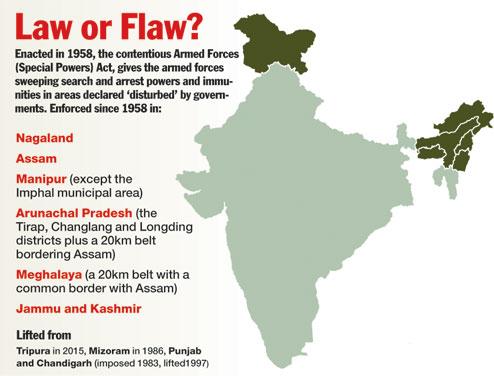

- Tripura revoked the Act in 2015 and Meghalaya was under AFSPA for 27 years, until it was revoked by the MHA from 1st April 2018.

- Currently AFSFA is in some parts of Assam, Nagaland, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh.

Key Provisions of the AFSPA Act

The salient features of the AFSPA act are:

- The Governor of a State and the Central Government are empowered to declare any part or full of any state as a disturbed area if according to their opinion that it has become necessary to disrupt the terrorist activity or any such activity that might impinge on the sovereignty of India or cause insult to the national flag, anthem or India’s Constitution.

- Section (3) of AFSPA provides that, if the governor of a state issues an official notification in The Gazette of India then the Central government has the authority to deploy armed forces for assisting the civilian authorities. Once a region is declared ‘disturbed’ then it has to maintain the status quo for a minimum of three months, as per The Disturbed Areas Act of 1976.

- Section (4) of AFSPA gives special powers to army officers in disturbed areas to shoot (even if it kills) any individual who violates the law / or is suspected to violate the law (this includes assembly of five or more people, carrying of weapons) etc. The only condition is that the officer has to give a warning before opening fire.

- Security forces can arrest anybody even without a warrant, and carry out searches without consent.

- Once a person is taken into custody, he/she has to be handed over to the nearest police station as soon as possible.

- Prosecution of the officer on duty for alleged violation of human rights requires the prior permission of the Central Government.

Disturbed Areas

Section 3 of AFSPA states that:

- An area to be declared as a ‘disturbed area’ is conferred on the Governor of the state or the Administrator of the Union Territory or the Central Government. The entire area or a part of it can be declared as disturbed by notification in the official gazette.

- The state governments can suggest whether the Act is required to be enforced or not. But under Section (3) of the act, their opinion can be overruled by the governor or the Centre.

- Initially when the act came into force in 1958 the power to confer AFSPA was given only to the governor of the state. This power was conferred on the central government with the amendment in 1978 (Tripura was declared a disturbed area by the central government, over the opposition by the state government).

- The act does not explicitly explain the circumstances under which it can be declared as a ‘disturbed area’. It only states that “the AFSPA only requires that such authority is of the opinion that whole or parts of the area are in a dangerous or disturbed condition such that the use of the Armed Forces in aid of civil powers is necessary.”

What is the Controversy Around the Act?

- Human Rights Violations:

- The law empowers security personnel, down to non-commissioned officers, to use force and shoot “even to the causing of death” if they are convinced that it is necessary to do so for the “maintenance of public order”.

- It also grants soldiers executive powers to enter premises, search, and arrest without a warrant.

- The exercise of these extraordinary powers by armed forces has often led to allegations of fake encounters and other human rights violations by security forces in disturbed areas while questioning the indefinite imposition of AFSPA in certain states, such as Nagaland and J&K.

- Recommendations of Jeevan Reddy Committee:

- In November 2004, the Central government appointed a five-member committee headed by Justice B P Jeevan Reddy to review the provisions of the act in the northeastern states.

- The committee recommended that:

- AFSPA should be repealed and appropriate provisions should be inserted in the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967.

- The Unlawful Activities Act should be modified to clearly specify the powers of the armed forces and paramilitary forces and Grievance cells should be set up in each district where the armed forces are deployed.

- Second ARC Recommendation: The 5th report of the Second Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC) on public order has also recommended the repeal of the AFSPA. However, these recommendations have not been implemented.

What are the Supreme Court Views on the Act?

- The Supreme Court has upheld the constitutionality of AFSPA in a 1998 judgment (Naga People’s Movement of Human Rights v. Union of India).

- In this judgment, the Supreme Court held that

- a suo-motu declaration can be made by the Central government, however, it is desirable that the state government should be consulted by the central government before making the declaration;

- the declaration has to be for a limited duration and there should be a periodic review of the declaration 6 months have expired;

- while exercising the powers conferred upon him by AFSPA, the authorized officer should use minimal force necessary for effective action.

Way Forward

- The status quo of the act is no longer the acceptable solution due to numerous human rights violation incidents that have occurred over the years. The AFSPA has become a symbol of oppression in the areas it has been enacted. Hence the government needs to address the affected people and reassure them of favourable action.

- The government should consider the imposition and lifting of AFSPA on a case-by-case basis and limit its application only to a few disturbing districts instead of applying it for the whole state.

- The government and the security forces should also abide by the guidelines set out by the Supreme Court, Jeevan Reddy Commission, and the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC).