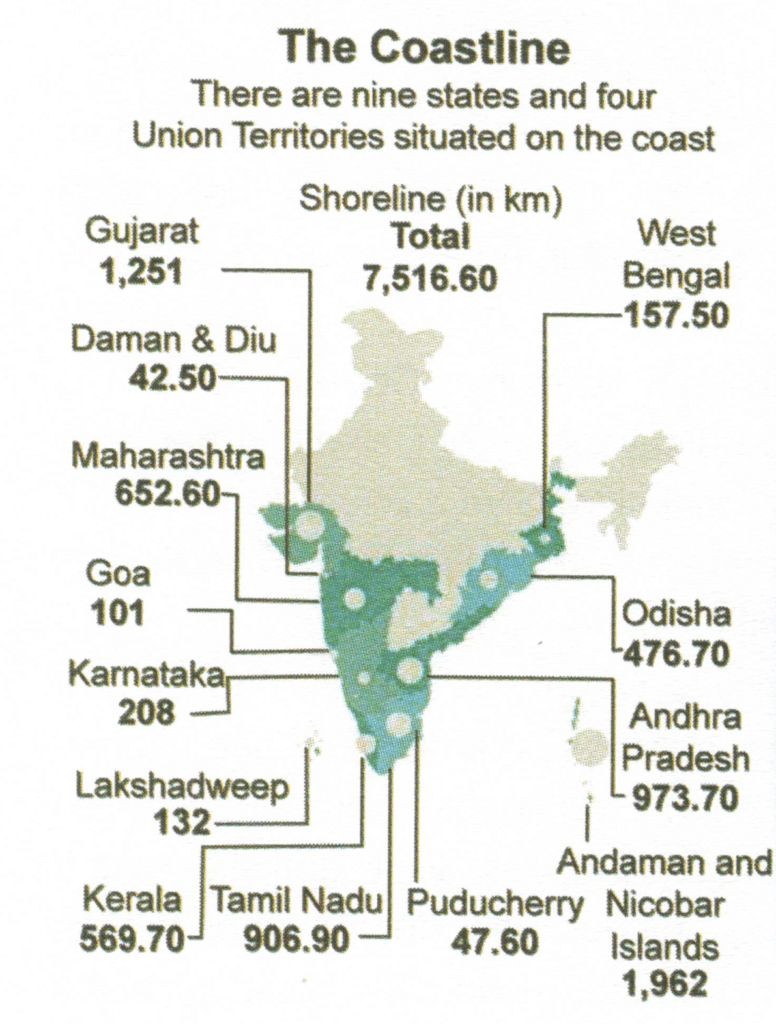

As a peninsular country, India has a vast coastline of 7516.6 km. India’s coasts have always been vulnerable to criminals and anti-national activities. Numerous cases of the smuggling of goods, gold, narcotics, explosives, arms and ammunition as well as the infiltration of terrorists into the country through these coasts have been reported over the years.

The smuggling of explosives through the Raigad coast in Maharashtra and their use in the 1993 serial blasts in Mumbai, and the infiltration of the ten Pakistani terrorists through the sea route who carried out the multiple coordinated attacks in Mumbai on November 26, 2008, are the most glaring examples of how vulnerable the country’s coasts are.

Smuggling of drugs and contraband, illegal unreported and unregulated fishing, and flow of migrants from neighbouring countries are other variables that underscore the importance for coastal protection.

The Indian government has been aware of the criminal activities that are carried out through the country’s coasts and had been implementing corrective measures from time to time. However, there have been some issues in the past as mentioned below:

- These measures have been mostly reactive and piecemeal in nature.

- Preoccupation with the defence and security of land borders had prevented the Indian policy makers from recognising the urgency of securing the coasts against sea-borne threats and challenges.

- The component of coastal security did not figure prominently in the national security matrix until the terror attacks of November 26, 2008.

The magnitude of the attacks of November 26, 2008, was so intense that the government was galvanized into putting in place a mechanism for securing the coasts. Since then, coastal security has become a buzzword in the national security discourse.

Various Threats to Coastal Security of India

India’s coasts have been susceptible to various kinds of sea-borne threats and challenges. This vulnerability stems from a number of factors, namely:

- The configuration of the country’s shoreline and its geographical location.

- Unsettled and disputed nature of some of India’s maritime boundaries.

- The existence of vital strategic installations.

- Increased maritime traffic along the coasts.

Maritime Terrorism

- Concerns about sea borne terrorist attacks have heightened the world over. The vulnerability of maritime targets, increased dependence on sea borne trade and commerce, and the relatively ungoverned high seas and un-patrolled coastal waters are some of the factors which add to this concern. Based on the study of the various incidents and patterns of maritime terrorism, potential targets for terrorist attacks can be identified against which the country has to be ever vigilant. These are as follows:

Attack on Commercial Centres

- Coastal raids on hotels, beach resorts, shopping malls in major coastal cities is a ‘well established naval method’, which the terrorists have carried out successfully although infrequently. In such raids, terrorists come ashore using small boats, seize a commercial complex such as a hotel, and take hostages. India is no stranger to such acts of terror having been exposed to similar attacks on November 26th, 2008.

Attack on Ports and Other Strategic Facilities

- Ports handling large volumes of traffic especially oil and other goods and having a large population centre in its vicinity are most valued targets for the terrorists. By targeting major ports, the terrorists could maximise economic damage. Besides ports, attacking oil supplies is another effective way of disrupting the global economy. Terrorists are aware of the political and economic benefits of attacking these strategic infrastructures and therefore , over the years, have targeted pipelines, oil platforms, pumping stations, and tankers in Iraq, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen. Naval bases, industrial hubs, and other strategic setups such as nuclear power plants are also potential targets for terrorists. The LTTE suicide bombers had frequently targeted Sri Lankan naval bases since 1990.

Attack on Ships

- Ships are soft targets for the terrorist groups as they have practically no means of protection. These ships could be hijacked, attacked by rockets, grenades and firearms, or packed with explosives and destroyed. Of all the tactics, hijacking in coastal waters or at high seas has been the most preferred means of terrorism. Terrorist groups have also bombed and sunk ships to generate publicity.

Piracy

- Indian Ocean Region is an ideal location for piracy as the region has attracted more capital and tourists and pirates have simply followed the money. Open waters, vast coastline, large distances, crowded sea lines, and most importantly, failed state have all created the perfect environment for piracy.

- In India, the shallow waters of the Sunderbans have been witnessing ‘acts of violence and detention’ by gangs of criminals that are akin to piracy. The gangs attack fishermen, hijack their boats, hold them hostage, demand ransoms, rob them of their catch and personal belongings, and sometimes kill them.

Armed Robbery

- Robbery in ships berthed in the anchorage areas are also a cause for concern as they expose gaps in the security arrangements of the affected ports and ships. Several cases of robbery have been reported from various ports in the country.

Smuggling

Indian coasts have been susceptible to smuggling. Gold, electronic goods, narcotics, and arms have been smuggled through the sea for a long time. Factors that have created a favourable atmosphere for the smugglers:

- Ban on the import or export of items such as gold

- High import duties especially on electronic goods

- High domestic demand for such items

- Traditional smuggling routes

- The availability of a wide range of sea-going vessels

- Lax coastal surveillance

Coasts and Smuggling

| Coast | Smuggled Items | Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Gujarat-Maharashtra | Gold, Heroin and Hashish | Proximity to the Gulf countries, Proximity to Pakistan, Highly indented shoreline, Well established criminal network |

| Tamil Nadu | Gold, Electronics, Spices and coconut, Textiles, Arms, Ammunition, Gelatine sticks, Detonators, Boat engines, diesel when LTTE was active in the region | Proximity with Sri Lanka, Boundaries are not clear to fishermen, Strong ties between Tamil people on either sides |

| Sunderbans | Rice, Diesel, Saris, Timber and Antiques | Difficult terrain, Porous borders, Strong linkages between people residing on either side of the border, Poor surveillance |

Trafficking

Trafficking of drug, human beings, wildlife and marine organisms is also prevalent along Indian coasts. This could be well represented in a tabular form below.

Coasts and Trafficking

| Coast | Trafficking |

|---|---|

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | Poaching of diverse marine species such as sea cucumbers, corals, fish, shells and crocodile |

| Gulf of Mannar | Poaching of Sea cucumbers |

| Sunderbans | Human trafficking Poaching of Wildlife—such as tigers, turtles, and protected species of fish such as shark and stingray |

| Gujarat-Maharashtra | Drug trafficking |

| Tamil Nadu | Human trafficking |

Infiltration

- To prevent infiltration, the Indian government implemented widespread security measures. The elaborate security arrangements on land forced the terrorists and illegal migrants to look towards the sea where security measures are comparatively lax, enabling them to ‘move, hide and strike’ with relative ease.

- The creek areas of Gujarat are highly vulnerable to infiltration. Geographical proximity to Pakistan and a terrain that is conducive for stealth movements make the region ideal for infiltration. The Indian security and intelligence agencies have also highlighted the fact that suspected members of Laskar-e-Taiba and other terrorist groups operating from Pakistan could infiltrate through Lakshadweep.

Illegal Migration

- The eastern and southern coasts face the problem of illegal migration. Pushed by political turmoil, religious and political persecution, overwhelming poverty, and lack of opportunities in their countries, Sri Lankan and Bangladeshi nationals have been migrating to India illegally for decades.

- Over the years, these refugees have become both a security as well as a humanitarian concern for the Indian government. Trafficking in drugs and human beingsin particular through the coast of Tamil Nadu-has registered an upward trend since Sri Lankan refugees started entering the state.

Refugee Influx

- Influx of refugees from Bangladesh has been going on since Independence, more so, during the independence struggle of Bangladesh in 1970’s. In the earlier decades, the inflow of Bangladeshis was mostly confined to the bordering North-Eastern states, the fencing of the border has forced the migrants to turn towards the sea, and land their refugee boats along the West Bengal and Odisha coasts.

Straying of Fishermen beyond Maritime Boundary

- The frequent straying of fishermen into neighbouring country waters has not only jeopardised the safety of the fishermen but has also raised national security concerns.

- Along the India-Pakistan maritime boundary, the lure of a good catch is the main inducement that drives Indian fishermen to cross the international maritime boundary into Pakistani territorial waters.

- Many security analysts fear that Pakistan’s Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) could extract information about various landing points in India from masters of these boats, these men could be brain washed and used as agents against India, the confiscated trawler could be used to sneak in terror operatives (along with arms) as they could enter into Indian waters without raising any suspicion.

- Indian and Sri Lankan fishermen trespassing into each other’s territorial waters is another big sore point in the relations between the two nations. Use of bottom trawlers which scrape the seabed and disturb the marine environment. Identified as an internationally banned Illegal, Unregulated, Unreported (IUU) fishing practice, bottom trawling is banned both in India and Sri Lanka. However, It is common knowledge that many Indian bottom trawlers fish in Sri Lankan waters. Indian fishermen defy prohibition and continue to fish beyond the maritime boundary claiming historical rights to the waters drawing the attention of the Sri Lankan authorities.

- In the case of the India-Bangladesh borders, the straying of Indian fishermen in Bangladesh’s territorial waters invariably not only draws the attention of that country’s maritime law enforcement and security agencies, but also invite attacks from pirates.

Conclusion

- India faces many threats and challenges from its maritime domain. Whereas some of these threats and challenges are obvious, others are potential in nature. The scope and intensity of the threats and challenges also vary. While threats – such as maritime terrorism – have the enormous ability to destroy national security, challenges like smuggling and the straying of fishermen can also jeopardise the safety of the nation.

- Thus, securing the country’s coasts and its adjacent seas from these threats and challenges requires

a comprehensive strategy. Over the years, Indian policy makers and security establishments have been engaged in devising policies and measures to put in place an effective response mechanism to deal with these threats and challenges.

Evolution of Coastal Security Architecture of India

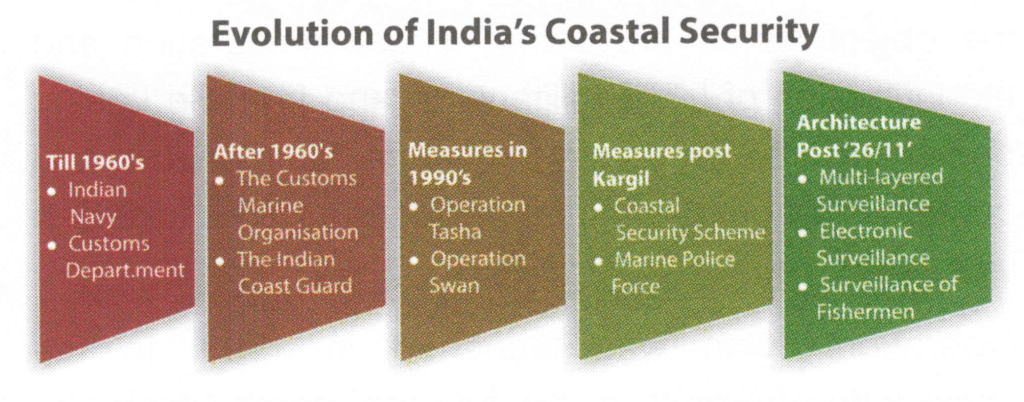

One of the earliest challenges to coastal security that India has had to encounter was sea-borne smuggling. The Customs Department and the Indian navy found it difficult to undertake successful counter smuggling operations because effective intelligence regarding the landings of contraband along the coast was absent.

Measures After 1960’s

The Government of India constituted study groups and committees, which recommended the creation of a specialised force, suitably equipped for carrying out anti-smuggling operations as the preferred solution.

Custom’s Marine Organisation

- The Customs Marine Organisation (CMO) was created following the recommendations of the Nag Chaudhari Committee, which recommended the raising of a specialised force as an effective instrument to counter sea-borne smuggling.

- Thus, the Gol created the CMO in August 1974, and mandated it to conduct anti-smuggling operation. CMO was merged with the newly created organisation Indian Coast Guards in January 1982 to avoid the duplication of efforts.

Indian Coast Guard

- A committee, under the chairmanship of K.F. Rustomji, was formed to look at the prospect of creating a coast guard as well as suggesting anti-smuggling measures. The committee observed that the lack of effective surveillance of the coastal waters and adjacent seas was one of the main reasons for heightened smuggling activities.

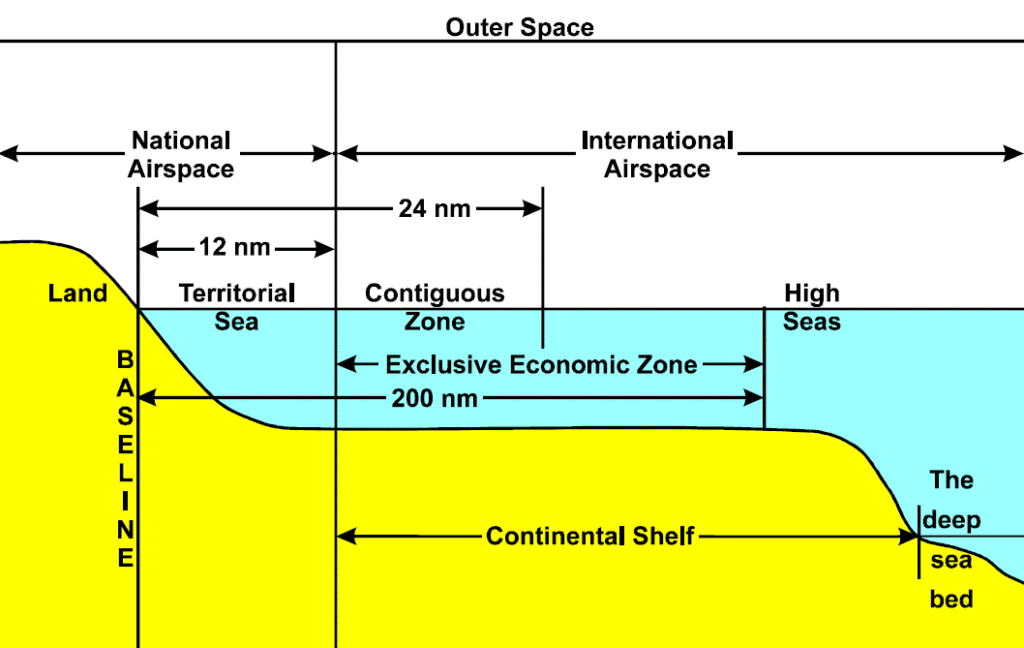

- The inclusion of a vast expanse of maritime area after the United Nations Convention for Laws of Sea (UNCLOS) recognised the concept of exclusive economic zone (EEZ) required a force that would be able to police it as well as safeguard the country’s interests within its limits.

- Thus, Indian Coast Guard was established, with the enactment of the Coast Guard Act, the organisation formally came into being as the fourth armed force of India in August, 1978.

Measures in 1990’s

- Indian navy launched Operation Tasha in 1990, which resulted in a layered concept of surveillance , with the objectives of preventing illegal immigration and the infiltration of LTTE militants to and from Sri Lanka; preventing the smuggling of arms, ammunition and contraband from the Indian mainland to Sri Lanka and vice versa.

- Operation Swan was launched in 1993, in the immediate aftermath of the Mumbai bomb blasts. Its aim was to prevent clandestine landings of contraband and illegal infiltration along the Maharashtra and Gujarat coasts.

Measures Post Kargil War

- In response to the Kargil Review Committee (KRC) report, which recommended a comprehensive overhauling of the country’s security system, Government of India set up a Task Force on Border Management, with coastal security being a part of it. The Task Force recommended creation of a Marine Police Force.

- Coastal Security Scheme (CSS) was launched in 2005 with an aim to strengthen infrastructure for patrolling and the surveillance of the coastal areas, particularly the shallow areas close to the coast.

- Under the scheme, assistance has been/is being given to all the coastal States to set up 73 coastal police stations 97 check posts 58 outposts and 30 operational barracks and to equip them with 204 boats, 153 jeeps and 312 motorcycles for mobility on the coast and in close coastal waters.

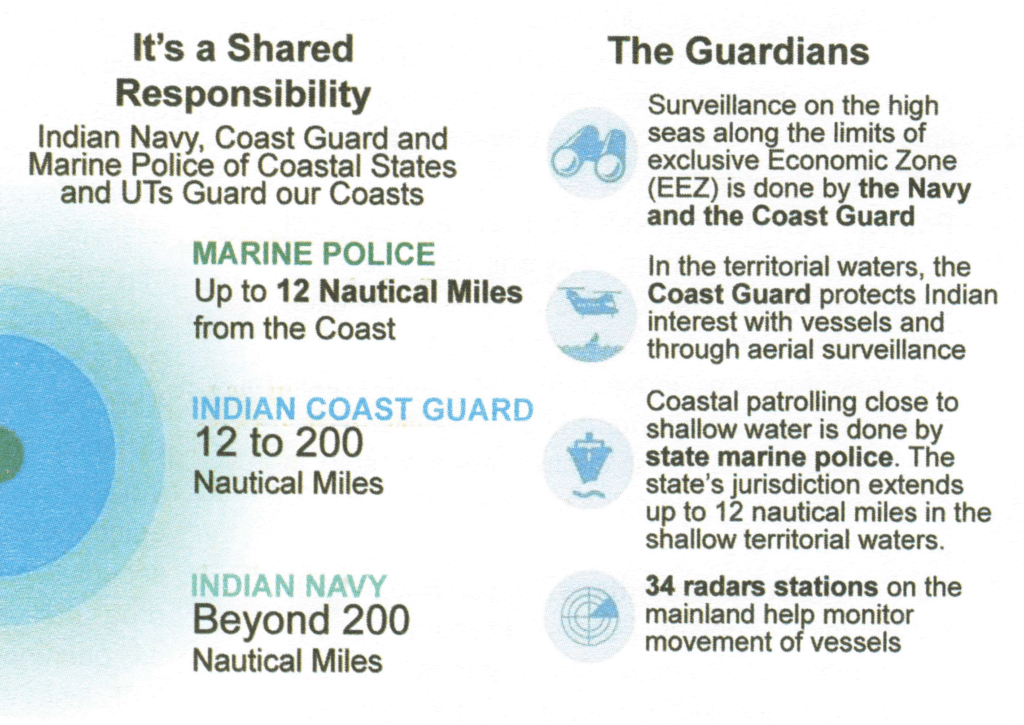

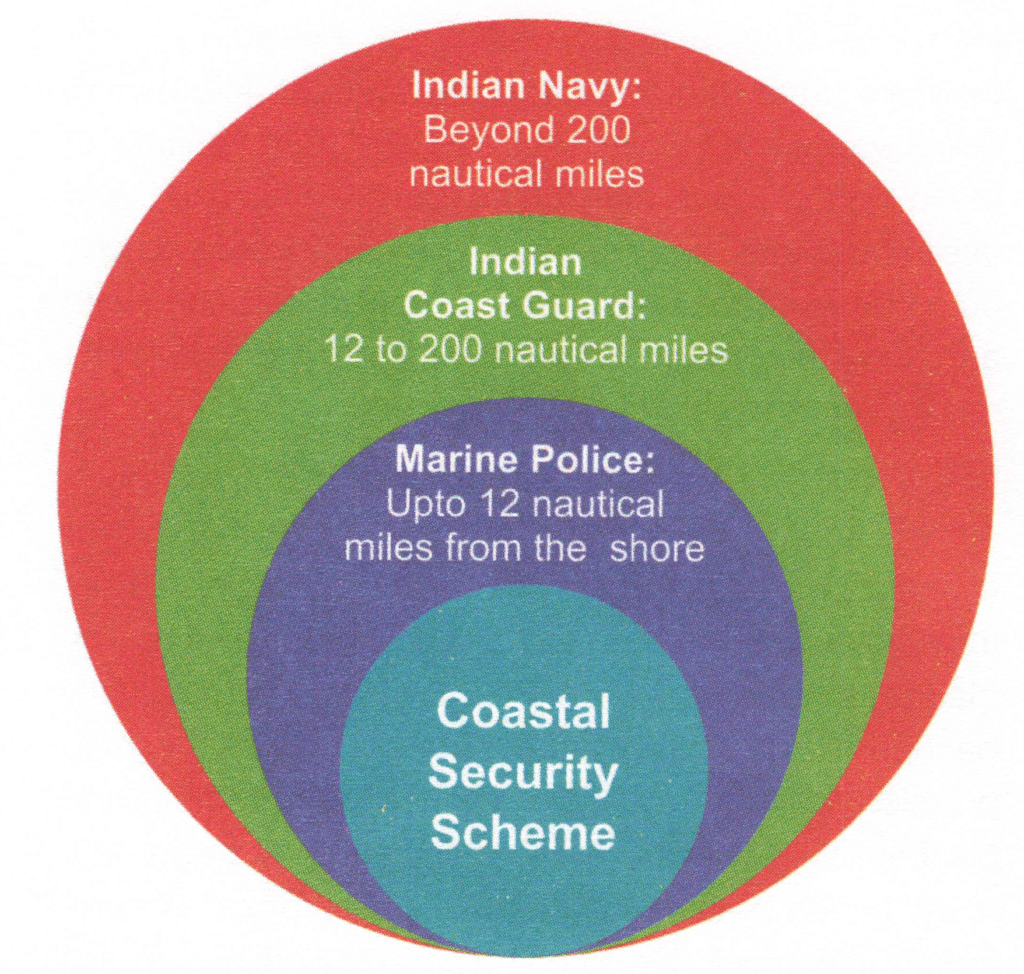

- A Marine Police Force was created under CSS, which required to work closely with the ICG under the ‘huband-spoke’ concept, the ‘hub’ being the ICG station and the ‘spokes’ being the coastal police stations. The marine police was mandated to patrol the territorial waters (12 nautical miles into the sea) and pursue legal cases pertaining to their area of responsibility according to specified Acts.

- Based on the inputs/proposals received from Coast Guard and the coastal States/UTs, Phase-ll of the Coastal Security Scheme has been formulated and has been approved by Government in 2010. Under Phase-ll of the CSS 131 Coastal Police Stations, 60 Jetties and 10 Marine Operation Centers have been sanctioned to all the coastal States/UTs.

Measures Post ‘26/11’

- The mind-set that coastal security is not an essential component of national security eventually changed after the terrorist attacks in Mumbai on November 26, 2008, a slew of measures were announced to plug the gaping holes in the existing coastal security system and introduce fresh measures to make it more robust. The implementation of these security measures resulted in the creation of a coastal security architecture comprising the following components:

Multi-Layered Surveillance System

Although, a multi-layered system of surveillance of the country’s maritime domain involving the Indian navy, coast guard, marine police, customs, and the fishermen was in existence but was working only on Gujarat coast. Under the system, the outer layer (beyond 50 nautical) was patrolled by the Indian naval and coast guard ships and aircraft; the intermediate layers (25-50 nautical miles) was patrolled by the ships of the Indian navy and the ICG as well as hired trawlers; and the inner layer i.e. the territorial waters (shoreline to 12 nautical miles), was patrolled by the joint patrolling team and later by the marine police. Post the 26/11 Mumbai attacks, the existing multi-layered arrangements have been further strengthened, as also extended to cover the entire coastline of the country.

- The Indian navy has been brought into the core of the coastal security architecture.

- It has been designated as the authority responsible for overall maritime security which includes coastal as well as offshore security.

- It is also made responsible for the coastal defence of the nation assisted by the ICG, the marine police, and other central and state agencies.

- Naval commanders-in-chief have been designated as the Commanders-in chief, Coastal Defence.

- The ICG has been assigned the additional responsibility for coastal security in the territorial waters, including areas to be patrolled by the marine police.

- It is required to raise a specialised force called the Sagar Prahari Bal for protecting its bases and adjacent vulnerable areas and vulnerable points.

- The marine police force, raised in 2005 under the Coastal Security Scheme to patrol the shallow waters, is being strengthened.

- For the security and surveillance of the creeks in Gujarat and the Sunderbans, the water wing of the Border Security Force (BSF) has been deployed along with eight floating Border Outposts (BOPs).

- All major and a few non-major ports are also being made International Ship and Port Facility Security code (ISPS-Code) compliant.

- An informal layer of surveillance comprising the fishermen community created following the 1993 Mumbai serial bomb blasts – has also been formalised and activated in all coastal state, named Sagar Suraksha Dal, comprising of trained volunteers who monitor the seas and coastal waters, share information about any suspicious activities or vessels at sea with security and law enforcement agencies, and also participate in coastal security exercises conducted by the ICG .

- Residents of coastal villages are also co-opted for gathering intelligence, the police in all states have formed Gram Rakshak Dais composed of a few ‘respectable’ villagers who keep a vigil on the village and adjoining areas, and serve as sources of information about criminal and anti-national activities.

Electronic Surveillance

- To provide near gapless surveillance of the entire coastline as well as prevent the intrusion of undetected vessels, the Government of India has launched the Coastal Surveillance Network Project. The network comprises the coastal radar chain, the Automatic Identification System (AIS), and Vessel Traffic Management System (VTMS).

- The coastal radar chain is supplemented by the National Automatic Identification System (NAIS) network. The NAIS would facilitate the exchange of information between vessels as well as between a vessel and a shore station, thereby improving situational awareness and traffic management in congested lanes along the country’s coastal water ways. In the later stages, the data generated by the static radar chain and the AIS sensors will be integrated with the data from the VTMS, which are being installed in all major and a few non major ports.

Monitoring, Control and Surveillance of Fishermen

- Monitoring the movements of thousands of fishermen and their fishing boats/trawlers which venture into the sea every day is essential to ensure fool proof security of India’s coastal areas. For this purpose, all big fishing trawlers are being installed with AIS type B transponders. As for small fishing vessels, are being fitted with the Radio Frequency Identification Device (RFID).

- Distress Alert Transmitters (DATs) are being provided to fishermen so that they can alert the ICG if they are in distress at sea. For the safety of the fishermen at sea, the government has implemented a scheme of providing a sub-sidised kit to the fishermen which includes a Global Positioning System (GPS), communication equipment, echo-sounder, and a search and rescue beacon.

- Coastal security helpline numbers 1554 (ICG) and 1093 (Marine Police) have also been operationalized for fishermen to communicate any information to these agencies. For the identification of fishermen at sea, a scheme for issuing biometric identity cards has also been launched.

Conclusion

- Indian policymakers did not take into serious consideration the various sea-borne illegal activities that were undermining the coastal security of the country for a long time.

- Thus, responses to the threats and challenges were formulated only after the crisis situation had become too intense to be ignored. Most importantly, many of the policies were formulated without preparing the ground for their implementation. This top down and reactive approach towards coastal security has resulted in several inadequacies in the coastal security architecture.

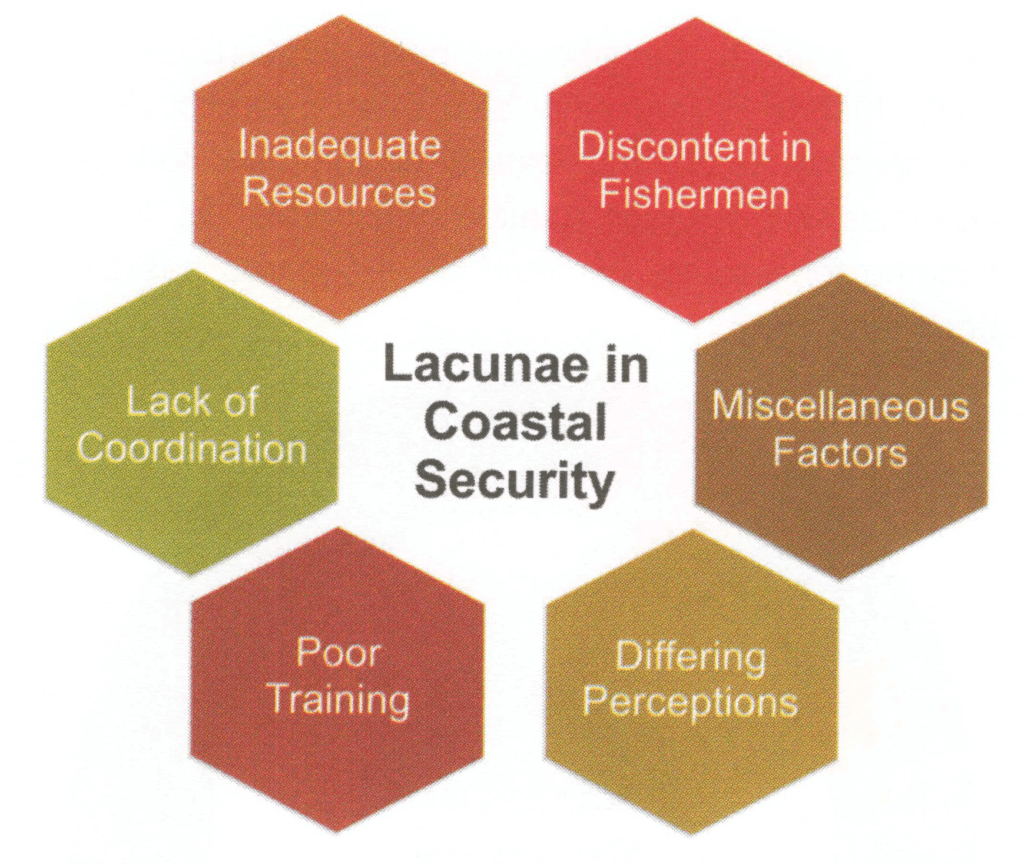

Lacunae in Coastal Security Framework

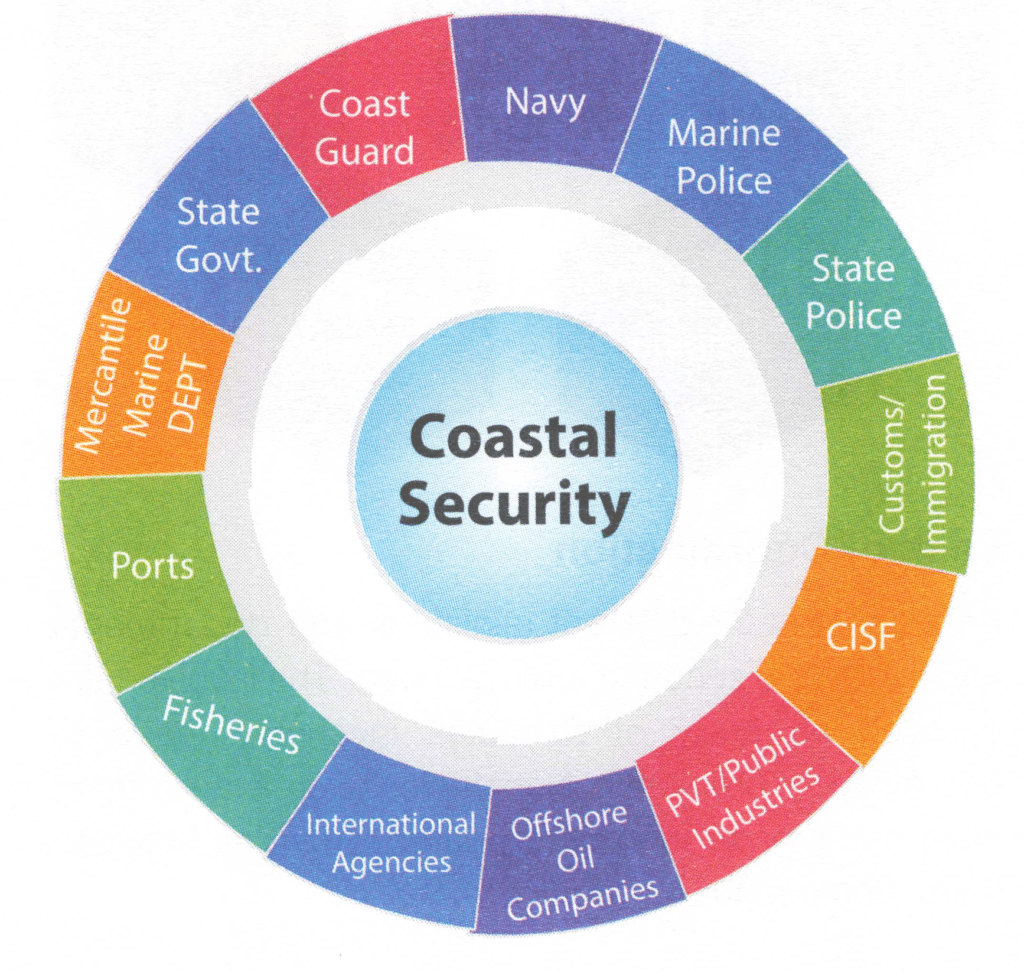

The Indian coastline had witnessed several breaches in its security in the past few years. Coastal security architecture built by India has certain inherent inadequacies which impair its effectiveness. These inadequacies may be categorised under broad categories such as the lack of coordination; differing perceptions; inadequate resources; poor training; discontented fishermen communities; miscellaneous factors; and absence of an integrated approach towards coastal security.

Lack of Coordination

An estimated 22 different ministries and departments are involved in securing India’s coasts. The involvement of such an array of agencies invariably leads to coordination problems. Nonetheless, constant efforts have been made to create greater synergies between them. Some of these efforts are:

- Formulation of Standard Operating Procedures: Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) have been formulated between the Indian navy and the ICG, and between the ICG, the marine police, customs, port authorities and other agencies to achieve optimum level coordination and the unhindered flow of information at every level.

- Conduct of Joint Coastal Security Exercise: Joint coastal security exercises under various names such as Sagar Kavach, Hamla, Raksha, Neptune, etc. involving all the maritime stakeholders have been regularly conducted in all the coastal states.

- Setting up of Coordination Committees: Coordination committees comprising of representatives of different agencies and departments have been formed at the state and district levels in the coastal states and union territories for enhancing cohesion and coordination.

- Establishing Joint Operation Centres (JOCs): Four Joint Operation Centres have been established in Mumbai, Kochi, Vishakhapatnam and Port Blair. These JOCs are primary coordination centres for all maritime operations, and are manned and operated by the Indian navy and the ICG.

These measures have not proven adequate for overcoming the strong forces of dissonance among the agencies. As a result, effective coordination remains an elusive goal. This lacuna is often cited as the reason for the failure of the coastal security architecture. The lack of coordination not only impacts the functioning of the system as a whole but also hampers the formulation of an integrated approach towards coastal security.

Reasons for Poor Coordination

- Tendency of each agency to zealously guard its own turf and any intelligence gathered, with the objective of scoring brownie points over other agencies.

- Do not even share simple information like details of sea-patrolling with other coordinating agencies, which ultimately results in duplication of efforts, as revealed by CAG.

- Absence of proper communication channels between the concerned agencies.

- Insufficient appreciation of the threat among concerned ministries and departments.

Inadequate Resources

- Insufficient resources have always been an impediment in the implementation of any scheme as it hampers the recruitment of manpower as well as the procurement of assets. The ICG faces shortage in its existing levels of manpower.

- Besides this, inadequate infrastructure in the form of the lack of office buildings, weapons, boats and vessels, jetties, workshops for repair and maintenance of boats, etc. also put constraints on the efficiency of all the agencies performing coastal security duties.

Differing Perceptions

- Another factor undermining the effectiveness of the coastal security mechanism is the differing perceptions among various stakeholders about their roles in ensuring coastal security. Differences in perception stem from their organisational culture and ethos.

- Every agency which is engaged in coastal security feels that it has different mandated duties, and coastal security is an additional responsibility that has been thrust upon it.

- The state governments in several coastal states have also been lackadaisical towards coastal security. Many of them do not perceive any kind of seaborne threats.

Poor Training

- The absence of trained personnel adept at sea patrolling and maritime combat operations is another factor that affects the performance of personnel. This is especially true for the marine police and the customs personnel.

- The lack of proper training is manifested by the extreme reluctance of the police and customs personnel to take up coastal security duties. Slow pace of training is an issue with the Indian Coast Guard because it delays quick induction of trained manpower in the services.

Absence of a Comprehensive Policy Formulation Mechanism

- An integrated approach to coastal security still eludes India. The Government of India had constituted the National Committee for Strengthening Coastal and Maritime Security (NSCMSC), but its mandate is limited to overseeing the implementation of various measures initiated in the wake of the Mumbai terrorist attacks.

- There is no coordinating body which could formulate national strategies for countering existing and emergent threats and challenges to national security as well as ensure smooth coordination among the concerned agencies involved in coastal security.

Discontent in Fishermen Communities

- Fishermen are considered the ‘eyes and ears’ of the coastal security architecture and, therefore, an integral part of it. They appear to be more comfortable interacting with officials of the Fisheries Department than with the personnel of the ICG or the Indian navy so they contact fisheries department first rather than contacting security agencies. They seem to be uncomfortable with the maritime security forces.

- In addition, the fishermen are also frustrated and angered by the poor response shown by the ICG to their distress calls. Moreover, the loss of their ‘traditional’ fishing harbours to sensitive and strategic establishments like naval bases, coast guard headquarters, coastal police stations, ports, etc. have also led to the generation of tension between the local population and these law enforcement and security agencies.

Miscellaneous Factors

Difficult terrain, seasonal weather patterns, administrative lapses, etc. all contribute towards introducing gaps in surveillance and the monitoring mechanism. One of the areas along the Indian coasts where all these factors play a role is in the Sunderbans. Let us take a case study of Sunderban.

- Difficult terrain, seasonal weather patterns, and administrative lapses.

- Topography of the Sunderbans does not lend itself well to human or electronic surveillance.

- The deployment pattern in the Sunderbans is such that no agency asserts its jurisdiction over large stretches.

- Under a protocol on Inland Water Transit and Trade (IWTT), Bangladeshi Vessels enjoyed free access to the waterways running through the Sunderbans en route to the Haldia Docks and the Kolkata Port. Though monitored by the BSF, but only along the border, after which they go unchecked for about 160 kilometres; this raises an important security concern.

- Relaxed patrolling and surveillance of the coastal waters during the rainy season During the season of southwest monsoon, the sea becomes very rough because of which most sea faring activities are suspended. Even the ICG and the Indian navy reduce the frequency of their patrolling of the sea.

Security of Non-Major and Private Ports

- The responsibility of providing security to 187 nonmajor ports rests on the states and union territories. However, in most of the non-major ports, physical protection arrangements-such as deployment of police personnel, fencing of their perimeter, monitoring of the access points, installation of screening and detecting machines, etc. do not exist.

Conclusion

- The coastal security architecture that India has established has been grappling with a number of inadequacies. The lack of coordination among agencies, differing perceptions about their coastal security roles, the lack of resources, poor training, growing discontentment among the fishermen, and miscellaneous factors such as terrain, weather, and administrative lapses have been severely affecting its ability to function effectively.

- The absence of an integrated approach to coastal security has aggravated the situation further . It is, therefore, imperative that corrective measures are urgently implemented to address these inadequacies , in this regard, a discussion of various international practices regarding coastal security could provide a better understanding of the ways to tackle the shortcomings in India’s coastal security structure.

Initiatives by Government to Strengthen Coastal Security

- At the apex level, the National Committee for Strengthening Maritime and Coastal Security (NCSMCS), headed by the Cabinet Secretary, coordinates all matters related to Maritime and Coastal Security.

- Joint Operations Centres (JOCs), set up by the Navy as command and control hubs for coastal security at Mumbai, Visakhapatnam, Kochi and Port Blair are fully operational. These JOCs are manned 24×7 jointly by the Indian Navy, Indian Coast Guard and Marine Police.

- Coastal patrolling by Navy, Coast Guard and marine police has increased sharply over the last few years. At any given time, the entire west coast is under continuous surveillance by ships and aircraft of Navy and Coast Guard. As a result, potential threats have been detected and actions have been taken to mitigate them in good time.

- Inter-agency coordination, between nearly 15 national and state agencies has improved dramatically, only due to regular “exercises” conducted by the Navy in all the coastal states. Nationwide, over 100 such exercises have been conducted till date since 2008, and this has strengthened coastal security markedly.

- In addition to continuous patrolling by Navy and Coast Guard, modern technical measures have also been implemented for coastal surveillance, by way of a chain of 74 Automatic Identification System (AIS) receivers, for gapless cover along the entire coast. This is complemented by a chain of overlapping 46 coastal radars in the coastal areas of our mainland and Islands.

- National Command Control Communication and Intelligence Network (NC3I) came up in existence which collates data about all ships and other vessels operating near our coast, from multiple technical sources including the AIS and radar chain. These inputs are fused and analysed at the Information Management and Analysis Centre (IMAC), which disseminates this compiled Common Operating Picture for Coastal Security to all nodes of the Navy & Coast Guard spread across the coast of India.

- Issuance of ID cards to all fishermen with a single centralised database, registration of fishing vessels operating off our coast and equipping fishing boats with suitable equipment, to facilitate vessel identification and tracking are some of the other steps taken.

- Fishing communities have become the ‘eyes and ears’ of our security architecture. This has been achieved by spreading awareness in these communities through coastal security awareness campaigns, conducted by the Indian Navy and Coast Guard, in all coastal districts of the country.

- During awareness campaigns fishermen have been strongly advised and warned not to cross the International Maritime Boundary as it is in the interest of their safety. Fishermen today own GPS receivers and are therefore fully aware of their positions at sea.

- The Navy and Coast Guard have also provided periodic maritime training to marine police in all coastal states. In order to have a permanent police training facility, Marine Police training institutes in Tamil Nadu and Gujarat have been approved by the Government recently. These will provide the Marine Police better facilities and infrastructure for professional training.

Conclusion

- Review of the coastal security apparatus in the country is a continuous process. A three tier coastal security ring all along our coast is provided by Marine Police, Indian Coast Guard and Indian Navy. Government has initiated several measures to strengthen Coastal Security, which include improving surveillance mechanism and enhanced patrolling by following an integrated approach.

- Joint operational exercises are conducted on regular basis among Navy, Coast Guard, Coastal Police, Customs and others for security of coastal areas including island territories. The intelligence mechanism has also been streamlined through the creation of Joint Operation Centres and multi-agency coordination mechanism.

- Installation of radars covering the country’s entire coastline and islands is also an essential part of this process. Around 34 radars stations on the mainland have been activated. Coast Guard Stations along the coastline are set up considering the threat perception, vulnerability analysis and presence of other stations in the vicinity. At present around 42 Coast Guard Stations along the coastline are functional.